Our “Scheidel moment”? – Peter Radford

If we are unfamiliar with what a “Minsky Moment” is then we should study the disaster of the Great Recession. While it’s true that economics has bumbled along pretty much unaltered since the dark years of a little over one decade ago – and, yes, I am well aware of the rumblings around the discipline’s edges – others have taken a bash at looking at facts.

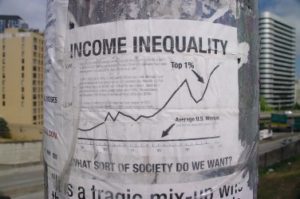

One of those people is Walter Scheidel who has given us a much needed historical context for our discussion about inequality. In a nutshell his extensive study of the history of inequality suggests that elites will always, and every- where, succeed in rigging society for their own gain. Whether they bother to hide their efforts behind socially accept- able or ideologically logical drapes is of no consequence: elites will find a way to enrich themselves at the expense of everyone else.

The forces that counter the elites are not, generally, benign democratic pressures. They are basic things like plagues, wars, and other devastations that upend the carefully constructed “norms” that form the basis of elite suppression of the masses. Such events sweep away the existing elite and create a space for a new struggle for power. During that struggle, whilst there is no elite to create new punitive rents or to exploit the broader population, brief bursts of relative equality break out.

Perhaps the most obvious example would be the shift that followed the Black Death in Europe in the 1300s. The scarcity of labour, especially skilled labour, after the plague had abated led to a remarkable period of relative wage equality in those nations that suffered through it.

Another good example would be the first half of the twentieth century during which the cataclysm of the world wars destroyed so much capital that elites needed a great deal of time to re-establish their hold over society and thus get back to their rent seeking ways. It was not until the neoliberal ascendancy after the Reagan/Thatcher led installation of anti-social policy that our contemporary elites could exploit society in the manner of elites of old.

The Scheidel Moment

Does the current global crisis caused by the novel virus spreading rapidly among us constitute a potent enough challenge to elite power and entrenched ideology that it opens a space for re-balancing societies away from the egregious inequality produced by neoliberalism? It’s too early to tell.

But there are rumblings and murmurs enough to suggest that, at the very least, a conversation might be beginn- ing. Here’s a quote from the New York Times this morning. The writer is Michelle Goldberg, a reliably socially oriented thinker …

“Since the election of Ronald Reagan, America has tended to value individual market choice over collective welfare. Even Democratic administrations have had to operate within what’s often called the neoliberal consensus. That consensus was crumbling before coronavirus, but the pandemic should annihilate it for good. This calamity has revealed that the fundamental insecurity of American life is a threat to us all.

“Margaret Thatcher famously said ‘there’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families.’ Tell that to the families effectively under house arrest until society gets this right.”

Naturally America is replete with suitable right-wing counterpoints. There are states whose governors still haven’t seen fit to react powerfully to the spread of the virus.

Yet the debate over what form an economic support plan should take, and the quite clear difference in impact the crisis will have on various income levels throughout the country, suggest a significant amount of unrest is building. And, perhaps, more importantly in terms of getting action, even the elite is realizing that its heady wealth and income are insufficient to insulate it from the shoddiness of the healthcare system they refuse to innovate or invest in. After all if a plutocrat cannot simply buy their own respirator because there aren’t any to be had, and if they sudd- enly have to make do like the rest of us, what’s being a plutocrat worth?

So, is this a Scheidel Moment?

Who knows. But it might be if we shout loud enough.

Source: https://rwer.wordpress.com/2020/03/25/our-scheidel-moment/

Commentary from Wayne McMillan:

I must take issue with Radford’s use of the term Minsky moment. This term became popular by financial commentators during the GFC and showed that none of them had seriously read any of Minsky’s publications. Minsky argued that in the upturn of a business cycle when the economy was humming along nicely this was false comfort, as the seeds for the downturn where being sowed. It was no simple event, but a series of stages within a business cycle that eventually built up to an economic downturn.

The word ‘moment’ might not be apt for describing what Walter Scheidel proposes. Scheidel I believe understands that societal change doesn’t happen overnight, but some- times a series of events or a cataclysmic event can trigger off a societal metamorphosis or a revolt.

During a pandemic it’s extremely unlikely that there will be any popular mass protests against the unfairness and injustices of the present socio-economic-political system.

However after the pandemic has taken its course, there may be a glimmer of hope for change, but this will depend on the unity and determination of the opposition confronting those in power. In the United States there are a considerable number of young people who want change and here in Australia young people are beginning to want change. However the question remains – has the younger generation got the cohesiveness, leadership and the right strategies/tactics in their political kitbag to bring about meaningful change.

I would suggest that Scheidel’s moment might be closer than we all think, but it may profit those contemplating societal change to look at the work of Gene Sharp who was the doyen of non-violent revolutionary action theorists. Many of the successful non-violent people power liberation campaigns in the 20th century were based on Sharp’s work and ideas.

Radford’s article despite its misuse of the term ‘moment’ has alerted us to a monumental well written historical work by a historian who gives us a grand historical picture of what might happen when power and wealth remains unequally shared for too long.

The old adage that you can fool some of the people for some of the time, but not all of the people all of the time, rings true in this case.