Systemically corrupt capitalism

Evan Jones

Capitalism has been analysed to death in academia and elsewhere. Thus we know that capitalism is structurally conducive to exploitation, to the production and reproduction of class-based inequality, to the degradation of nature, and so on. Such analysis is of capitalism at its purist.

Marginalised is the plunder. Widely acknowledged is the historical plunder that generated capital for the takeoff. But when booty from brutal early colonialism, the slave trade and from the enclosure of the commons feeds into capitalist mining, manufacture and agriculture, the naked plunder doesn’t cease.

My interest in this seeming side issue has developed since 2000 when I heard from my first bank victim after he had read an academic article of mine on farmer finance. I wrote about the subject, heard from more victims, and the dialectic has continued to this day. I have thus become atypically knowledgeable about malpractice, and indeed criminality, in the Australian banking sector.

Corruption in banking

Corruption in the Australian financial sector is not an aberration but an integral dimension of its modus operandi. Three factors lie behind banking’s criminal tendencies.

First, there is the special character of banking. Credit is an indispensable facility, so an essential public service is being delivered by companies with private motives. Moreover, the lender-borrower relationship is asymmetric. On home mortgages, the lender readily engages in predatory lending, capturing unsuitable borrowers, in addition fabricating figures and falsifying documents.

Regarding small business or farmer borrowers, the relationship is profoundly asymmetric. The lender takes customer assets as security over any loan. The lender will perennially induce the business borrowers to include the family home (and possibly that of the parents) as bank security.

The bank can default the business/ farmer borrower at will, with a variety of mechanisms at its disposal. The defaulted business borrower is subsequently left without the business and homeless, forced onto public welfare. This practice is not incidental but preplanned and pervasive.

In short, a banking licence is the perfect vehicle to both install and legitimate a criminal racket.

Second, inbuilt banking corruption has been facilitated by comprehensive deregulation (including privatisation) of the sector, following the 1981 Campbell report. A previous culture that kept malpractice under control was being dismantled in the 1970s and the process sped up with deregulation. Admittedly, internationalisation of finance and externalisation of workforce hire were inevitable, but no thought was given to the reconstruction of a culture of competence and integrity. Corruption set in from day one of deregulation, not least with the flogging of foreign currency loans to unsuspecting small business people and farmers.

Third, the corporation per se is a natural vehicle for corrupt practices, of which more below.

Banking’s comprehensive support team in corruption

Bank plunder occurring on an ongoing basis needs a wide-ranging support team. The process will be facilitated by a spectrum of ‘professional’ bodies dependent on the bank teat – the law firms, valuers, receivers, real estate agents – and even some categories of public officials (sheriffs and bankruptcy

trustees). On occasion, some banks will even consort with known petty criminals in the ‘enterprise’ of customer default. All are complicit in the plunder, obtaining their share of the booty.

Bank plunder is dependent on tame regulators, which banks have in ASIC and APRA, and in complicit mediators, which banks have in FOS and Farm Debt Mediation services.

Bank plunder is dependent on a supportive court system, which banks have. The judiciary is suckled in contract law, for which plunder does not exist. A major Australian banking law textbook claims:

“ [The lender-borrower relationship] is based on contract and the parties deal at arm’s length, with no obligation on either party to act with any higher duty to each other than that required by the law of the marketplace. “

It is implicit but unspoken that the law of the marketplace is the law of the jungle.

Some bank litigation judgments in favour of the banks are so outrageous that one surmises that corruption has pervaded the judiciary itself.

Bank plunder is dependent on a compliant political class, which banks have to date. Governments have passed assorted legislation with the formal intent of cleaning up bank behaviour, but they are of little substantive value. In the meantime, bank donations roll into political party funds, and the ‘revolving door’ practices intermingle sometime public officials and banking institution employment.

The end result is that bank criminality, sometimes formally illegal, sometimes formally legal, is legitimised, and thus effected with impunity.

We might readily accept the maxim ‘the state is an instrument of class rule’, but it helps to outline the fine detail that gives that maxim substance.

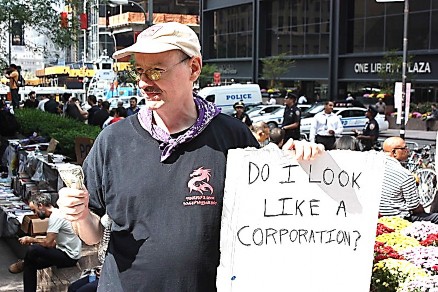

The corporation per se conducive to criminal practices

The creation and evolution of the joint stock corporation in the mid to late nineteenth century transformed capitalism. Confrontation with its adverse implications and subsequent resistance appears to have been most significant in the United States.

The pivotal signal of the new era was the 1886 US Supreme Court judgment (via a legalistic ruse) in Santa Clara County vs. Southern Pacific Railroad that a private corporation is a natural person under the US Constitution. A race to the bottom by US States, in particular New Jersey and the hick State of Delaware, to attract company incorporation led to the unprecedented phenomenon of corporate chartering with no restrictions as to activity, inter-company ownership structures or longevity.

Corporate personhood, then and now, builds a relatively impermeable wall behind which wilfully negligent actions with large-scale adverse consequences and strategic criminal actions (including the overthrow of governments) by real persons can flourish.

The institutionalist economist William Dugger has labeled the corporation ‘organised irresponsibility’ – perceptive of its character, but ultimately too kind.

A 2004 book (and associated documentary) by the Canadian lawyer Joel Barkan, The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power, exposed the Frankenstein created with corporate personhood.

To Edward, Baron Thurlow (the British Lord Chancellor 1778-92) is attributed the apt declamation: “Did you ever expect a corporation to have a conscience, when it has no soul to be damned, and no body to be kicked? ”

The extreme degradation of the workforce through incapacitation or death has, of course, been a permanent feature of corporate capitalism.

There are the perennial catastrophic human, social and environmental disasters. Think thalidomide (1957-),

Bhopal (1984), the EXXON Valdez oil spill (1989), the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill (2010), and the BHP/Vale dam-bursting village destruction in Brazil (2015). These events are not atypical accidents but integral.

And confront the spectacular series of manoeuvres by which EXXON sought to avoid culpability, by the end of which it had successfully reduced its liability to a pittance. Or confront the history of Big Tobacco a masterpiece of entrenched strategic criminality.

Ditto, more recently, Monsanto.

—–

Capitalism is the astounding belief that the most wicked of men will do the most wicked of things for the greatest good of everyone.

John Maynard Keynes

——

The essence of capitalism is to turn nature into commodities and commodities into capital. The live green earth is transformed into dead gold bricks, with luxury items for the few and toxic slag heaps for the many. The glittering mansion overlooks a vast sprawl of shanty towns, wherein a desperate, demoralized humanity is kept in line with drugs, television, and armed force. ― Michael Parenti, Against Empire

Integration of high street and back streets, finance at its centre

We tend to place the deeply ‘shady’ arena of mafia-style operations and stock exchange-listed corporations in separate boxes. But there is no clean dividing line, with the two arenas intermingling. Finance is a key match-maker, with money-laundering and tax evasion flowing through the same channels as the financing mechanisms of ‘respectable’ commerce and industry – mediated by complex financial instruments incomprehensible to the outsider. In effect, in every concrete pour there is a dead body or two.

The Canadian R T (Thomas) Naylor is a rare author to emphasise the integrated character of global finance. The preface of his Hot Money and the Politics of Debt notes:

“ A ball of hot money rolls around the world. It seeks anonymity and political refuge; it dodges taxes and sidesteps currency controls; it rolls through shell companies and numbered accounts, phoney charities and religious foundations. And it is kept rolling by misguided policy-makers and white-collar criminals, by gunrunners and drug agents and third-world political elites preparing for retirement. “

Naylor names Switzerland as historically pivotal in the nurturing of such a structure, and accuses the International Monetary Fund of institutionalising a regime of redistribution of the burden from criminal parties to the innocent.

Naylor has an academic post (McGill University), but his admirable investigative orientation and skills has remarkably left him little known.

Dr Evan Jones is an Honorary Associate in Political Economy at the University of Sydney, having retired from the Political Economy Department in 2006. He is also an ERA patron. His current writing interests include corruption in the Australian banking sector.

Source: https://www.ppesydney.net/systemically-corrupt-capitalism/

This article is reproduced with the permission of the author. Part 2 will appear in the next issue.