Sectoral balances in macroeconomics

Philip Lawn

Assuming net exports are zero (which they should be – after all, to net export is to give up more useful stuff to foreigners than you receive in return), the reason why a currency-issuing central government must run budget deficits on average is because the private sector – as the user of a nation’s currency – cannot continue to accumulate debt. If the private sector, in aggregate, wishes to net save and is determined to do so (i.e., determined to reduce its current spending to whatever level is required to positively net save), a currency-issuing central government cannot run a budget surplus no matter how hard it tries (witness what is happening in the EU).

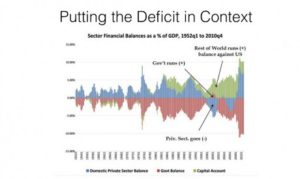

There is a dictum in macroeconomics as authoritative as the relationship E = mc2 in physics, namely: Injections = Leakages. This may be expressed in algebraic terms as

I + G + X = S + T + M

where I = private sector investment in productive capital goods, G = government spending, X = exports, S = private sector savings, T = government taxation, and M = imports. If you don’t believe that injections must equal leakages (as some people wrongly assert), have a look at the figure at the end of this article. If you rearrange the above equation, you get

(G – T) = (S – I) – (X – M)

If net exports = 0, X = M and we are left with:

(G – T) = (S – I)

As you can see, the government’s budget deficit/surplus mirrors the private sector’s net saving/dissaving out of current income. If the private sector wishes to have positive net savings of, say, 100 (S – I = 100), this is only possible if the government’s budget deficit is 100 (G – T = 100). If the government attempts to run a surplus of 100 (G – T = –100), which might involve cutting G, national income falls. This reduces the income that the private sector has at its disposal to finance both its spending and its net saving. Thus, a cut in government spending means that the private sector will not have sufficient income to finance, out of this income, its spending and net savings desires. It must therefore abandon one of these desires.

- Let’s assume that the private sector decides to maintain its spending desires and abandon its net savings desires. This characterises Australia and most of the industrialised world from 1995-2007. By maintaining its spending, national income stays buoyant, unemployment remains low, the government achieves its budget surplus, and the likes of Peter Costello parade around as if they are greatest thing since slice bread. But it is only achieved by having the private sector accumulate debt unsustainably. Once the private sector can no longer increase debt levels to maintain its spending desires, it stops spending. It then (2008 onwards) focuses on meeting its net savings desires to pay down its accumulated debt. This was the ultimate cause of the GFC – the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the USA was just a trigger. Thank you the Peter Costellos of the world!

- The period from 2008 onwards is where the private sector decided to satisfy its net savings desires and abandon its spending desires. Now the positive net savings of the private sector is, say, 100 (S – I = 100); the reduction in private sector spending lowers national income, unemployment rises, and the government can no longer run a budget surplus regardless of how hard it tries because tax revenues plummet (i.e., G – T must equal 100). Are you reading this Wayne Swan (Chris Bowen)? And more depressingly, are you reading this mainstream macroeconomists of the world [i.e., those academic and practicing macroeconomists of the world who have forgotten/ignored their MACRO 101 principles because it gets in the way of their ideological principles and the development of elaborate (mathematical) economic models that are designed to support their ideology]?

How do I know that the mainstream macroeconomists of the world have abandoned first-year undergraduate principles? Because none of them could foresee the global financial crisis (GFC). Modern monetary theorists could see the GFC coming years in advance. Was it because they are all brilliant? No, because any reasonably competent first-year undergraduate student could see it coming (providing they weren’t brainwashed by their mainstream macro- economics lecturer).

Moral of the story: If the private sector wishes to net save, which is necessary to prevent the private sector from accumulating debt unsustainably, macro-economic stability (and full employment) requires currency-issuing central governments to run budget deficits, which they can do forever because they are the only entity in the national economy (except for EU nations) with the legislative capacity to counterfeit the nation’s currency. Currency-issuing central governments have access to a bottomless pit of the nation’s currency – and for good public-advancing reasons. It is their job to net spend to whatever level is necessary to maintain macroeconomic stability and full employment and to provide an adequate supply of high-quality public goods and infrastructure. Once they have achieved this objective, they should not spend a cent more, not because they can’t find the money to do so, but because they face a real resource constraint (like everyone else) in which case net spending beyond the maximum necessary simply pushes total spending within the economy (i.e., public sector + private sector spending) beyond the economy’s productive capacity, which is inflationary. The other major issue is to make sure total spending within the economy does not exceed the nation’s ‘sustainable’ productive capacity, which, for most countries, is much less than current GDP levels. ‘Productive capacity’ and ‘sustainable productive capacity’ are two different things. Operating where total spending remains at the economy’s sustainable productive capacity won’t be achieved by cutting government spending. It can be achieved via income redistribution and making sure, along the way, that net government spending always accommodates the spending and net savings desires of the private sector (both of which will have to be less in the future if most of the world’s economies are going to be ecologically sustainable).

Assoc Prof Philip Lawn is an ERA member and ecological economist attached to the Flinders Business school, Flinders University of SA