Monetary and fiscal policy frameworks for Australia part 1

John Haly

In September 2022, the Reserve Bank of Australia was opened to public assessment. The submissions were to be part of a review announced by Treasurer Jim Chalmers in July. What follows is largely verbatim from my submission at the end of October. This will be published along with other reviews on the RBA review website in the week of December 5th. The Review Panel – comprising Renée Fry-McKibbin, Carolyn Wilkins and Gordon de Brouwer – assesses those submissions. Certain aspects of my original review used in-house vernacular, presuming a specific internal bank knowledge. I have added explanations of those concepts to facilitate a better understanding of this two-part series. Beyond these additional explanations, this is essentially the content of my submission. There are more embedded links in the digital version of this submission [1] than initially provided to the RBA to aid further exploration.

Themes

This submission covers Monetary policy frameworks such as adherence to the NAIRU and neoclassical “gold standard” mentality over that of monetary sovereign fiat economies. It covers RBA and Government communications about Finance Franchise myths on Banking, in general. It is critical of the Board composition based on bias in inappropriate neoclassical education and the selection of business representatives instead of economists trained in the issues of fiat economies. Finally, it reviews the Interaction of monetary and fiscal policy with respect to RBA’s performance in applying monetary policy where fiscal policy is more appropriate. As a former employee of the Reserve Bank, I have some

knowledge of the inner workings of the Reserve Bank. I understand that the review of the Reserve Bank of Australia is underway to improve monetary policy and its success at realising its goals, governance by the Board, culture, leadership, and recruitment practices. Such a broad range of objectives has yet to be approached since the smaller incidental 1981 Campbell inquiry and before that, presumably at its inception in 1960.

Curtin

Over the last century, Australia’s Central Bank and economy have undergone many changes. In the previous World War, the Curtin Government asserted Commonwealth power over banking, which led to Ben Chifley’s later decision to legislate to nationalise the commercial banks, which effectively asserted Commonwealth control over money and credit creation as per the Commonwealth Bank Act of 1945. However, such nationalisation was later defeated in 1949, as the book “Curtin’s Gift” by John Edwards says on p141:

“Though the post-war Menzies Government amended Chifley’s central banking legislation to reintroduce a board, the Commonwealth’s last-resort power to direct the bank was retained in the legislation and remains today.

The Commonwealth Treasurer has conferred on the bank an independent authority to make monetary policy, but it is a conditional independence to pursue a policy of low inflation, sustainable output and employment growth.”

Curtin had also argued for two other changes:

- Commit to a full employment policy to improve living standards and raise national development.

- A floating exchange rate to free Australia from the fixed exchange rate with the British pound

Ben Chifley implemented the Full employment policy following Curtin’s full employment paper being submitted to Cabinet in March 1945. Prior to the rise of Neoliberalism during the 1970s, unemployment remained dominantly at 2% (notably without substantial inflation).

Unemployment rate and NAIRU

This leads to the Reserve Bank’s first failure, which is its commitment to the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU). The RBA’s adherence to the economic self-deception espoused by the Phillips Curve model falsely supposes a trade-off between inflation and unemployment exists. That trade-off was initially set at 6% unemployment, then later 5%, and then for some 4% despite the evidence of Australian history. The NAIRU is a systematically flawed perspective on inflation generated by a nation’s economy approaching full employment that should have died in Australia in the 1950s. Specifically, after Ben Chifley’s success with the Full Employment policy in Australia demonstrated for 25 years, full employment did not accompany rampaging inflation. The Menzies government nearly lost an election when unemployment, rose to 53,000 people, or 3%, at the end of 1960. But it eventually settled back to 2%. Australia abandoned the Full Employment policies in the early 1970s. This led to increased unemployment and significantly growing inflation during the next decade. Supposedly this use of the Phillips curve fell out of favour after the great stagflation of the 1970s.

Instead, this zombie economic perspective has been raised from the dead, evidenced in 2022 with the prospect of the RBA using that justification for raising interest rates. All purportedly to manage a disquiet of ABS’s unemployment measure at 3.5%. Notably for a working labour force exceeding that experienced by Menzies in 1961 by a factor of three. PM Albanese’s claim in 2022 of the Job Summit was to seek a “Full Employment Summit” but baulked at the solution of the Curtin Government. Unfortunately, the neo-liberals of the political Party and of the Bank adhere to the conservative myth of the NAIRU.

Instead of NAIRU, we should consider NAIBER – as a better alternative perspective, especially as the Bank incorrectly suggests we are already “fully employed”. [See Bill Mitchell’s analysis: Never trust a NAIRU estimate]. Beyond Prof Mitchell’s frequent analysis of the NAIBER, Prof Steven Hail’s book “Economics for Sustainable Prosperity” explains it on page 242:

“[The acronym] NAIBER stands for the ‘Non-Accelerating Inflation Buffer Employment Ratio’. The buffer employment ratio replaces the unemployment rate with the ratio of workers in the job guarantee scheme relative to the total available labour force. This is the replacement of our existing buffer stock of the involuntarily unemployed and the underemployed with an employed buffer stock of workers within a publicsector job guarantee. The scheme would be a shock absorber for the economy expanding to employ workers when they have been shed from the private sector during a downturn, and contracting automatically as the private sector absorbs labour from the job

guarantee scheme in an upturn. Ecological modern monetary theorists have referred to an ecologically sustainable NAIBER, or ESNAIBER, in the context of a job guarantee as an element in a transition to an ecologically steady-state economy, given the ecological constraints referred to above.“

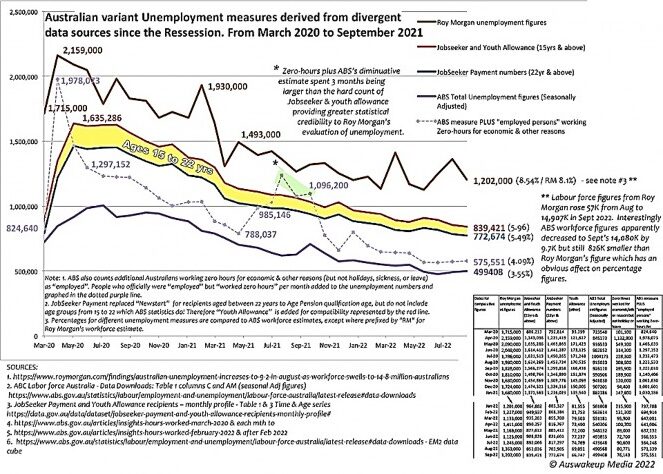

The goal of “full employment” has now been achieved if you conclude that the ABS statistics truly measure domestic unemployment. However it is instructive to look at the graphs and my articles covering what should have resulted from the Job Summit [my article and graphs: Stagnating Summit’s Shortfalls].

This is why “what gets measured” is essential. I will not go into detail about the shortcomings of the ABS statistics as they are probably already known and well understood; and if not, the article aforementioned herein should inform you. Raising interest rates as a strategy to deal with different forms of inflation is problematic at best. The link between spending and interest rates is unreliable and unpredictable. Interest rates affect both supply and demand. The economic modelling of “supply and demand” is only relevant to highly atomised markets with many participants, like the primary sector.

Secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy follow different models.

Changes in interest rates can have a reverse effect on inflation. Higher interest rates only affect people possessing variable interest rate debts. They don’t affect fixed interest rate debt and people with no immediate financial obligation. Higher interest rates increase the income of creditors and redistribute income to the wealthier, rentier class, exacerbating inequality.

Also, higher interest rates reduce the incentive to undertake debt and may cause “distress borrowing” to service existing debt or keep businesses afloat. The resulting Ponzi balance sheets do a disservice to the economy, and all of the above risk yet another recession. The government should be applying fiscal, not monetary, policy to these issues rather than allowing the RBA’s adherence to the disproven NAIRU theory collapse our economy into a greater level of inequality.

FIAT economy

Paul Keating’s decision to float the Australian currency in 1983 meant that Australia had entered a new economic space. We became a monetarily sovereign, fiat economy, no longer tied to any other currency or a gold standard (which even America had abandoned with the collapse of the Brenton Wood framework in 1971). The implications of which even the Bank of England acknowledges, even if neither the government’s political rhetoric nor the RBA acknowledge it. [see the Bank of England video: Money in the modern economy: an introduction – Quarterly Bulletin] Instead of shifting into this new space and engaging with this new paradigm of fiat economies, the neoclassical economic conversation stayed with the decades-old “gold standard” economic model. Still, neoclassical economics guides the decisions of the Reserve Bank’s mission to “pursue a policy of low inflation, sustainable output and employment growth.” [see “Curtin’s Gift” by John Edwards, p142] Problematically, even members of the RBA board need to understand the basics of modern monetary systems [Prof William Mitchell: The RBA has no credibility and the governor and board should resign].

The Reserve Bank’s role as the currency issuer for the government has been misunderstood by the business board appointees blinded by the tunnel vision of their experience as currency users in the business community. Most of the board are business people (five in number), three are neoclassical economists (Michele Bullock, Ian Harper and Dr Lowe), while Dr Steven Kennedy’s PhD was in the economic determinants of health, which is not precisely about financial systems. So none of the board has formal training in the economics of fiat economies or modern monetary economies. But that isn’t to say their experience on the board has yet to give them insight.

Some suggest the RBA is best served with board members selected on the basis of expertise in modern monetary fiat economics rather than as political appointees owing to relationships with former Prime ministers. To this day, neoclassical economics still guides the decisions of the RBA’s mission to pursue a policy of “low inflation, sustainable output and employment growth” but has universally failed to achieve what Curtin, Chifley and Menzies did for nearly three decades. Banking is widely misunderstood as a heavily regulated franchise industry acting as an intermediary between scarce private capital and borrowers. Modern finance is relatively scarce, and depositors are the source of money supplied to borrowers. [see Cornell Law School paper: “The Finance Franchise”].

My RBA letter continued to explore more of the money and banking myths believed by the public. The letter reviewed the recent quantitative easing while serving the needs of the highly financed wealthy. It did sadly little for the well-being of the larger Australian public. These are available in the RBA Review, pt2 (reference 2).

References:

Links to items and words used in this article (and in pt2, appearing in the next issue) are accessible from the original references.

John Haly is a qualified multimedia and graphic designer, as well as video and film producer and freelance journalist He has published extensively on a range of economic, political and social issues. John is secretary of the film collaborative, NAFA, and is a founding member of the Australian Arts Party. He also possesses a B.Bus degree, and is studying for the degree of Master of Economic Sustainability.

Pingback:Choosing Unemployment: Part 1 – What of Job Seekers? - Australia Awaken - ignite your torches

Pingback:Positing Job Guarantee Antecedents - Australia Awaken - ignite your torches

Pingback:The Flaws of Universal Basic Income - Australia Awaken - ignite your torches