Keen versus Krugman – John Balder

The following extract, made by John Balder from his recent RWER paper [1], appeared in the RWER blogs site [2].

To explore the origins of the global financial crisis, the first step is to specify the relationship between banking, money and credit. According to the mainstream view, a bank serves as an intermediary between a borrower and a lender. As a pure intermediary, a bank has no impact on real economic activity.

This view – taught in most Economics 101 textbooks – implicitly assumes that money is available in finite quantities that are regulated by the central bank.

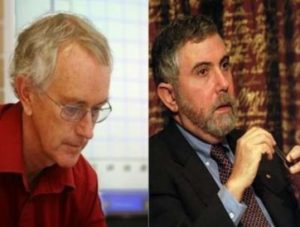

Several years ago, Paul Krugman and Steve Keen engaged in an enlightening back-and-forth about banking, money and credit. The discussion examined whether banks lend existing money or newly create the money they lend …

In support of the mainstream view, Krugman (2012) casually asserts: ‘Think of it this way: when debt is rising, it’s not the economy, as a whole borrowing more money. It is rather, a case of less patient people – people who, for whatever reason want to spend sooner rather than later – borrowing from more patient people.’

Krugman notes [asserts] that banks lend existing money as intermediaries between borrowers and savers. In other words, [that] a bank must have $100 in deposits before it can make a loan for $100 (deposits create a bank liability, needed for a bank to create an asset).

This viewpoint implies that money is neutral and can be ignored, as it has no relevance for real economic activity.The view seems to be intuitive, in fact almost obvious; after all, if I do not have $10, I cannot lend it to you.

Conversely, Keen (2011) argued that banks newly create the money they lend. If true, this suggests that moneycreation impacts real economic activity and is not neutral. But how does a bank ‘create’ money? When a bank makes a loan, it simultaneously creates a deposit (which is money) for the borrower in an identical amount.[3] For example, if I borrow $10,000 from my bank, the bank creates a deposit account in my name with $10,000 in it. In creating credit, a bank necessarily creates a deposit and thus, money. This is how double-entry bookkeeping works. Loans create deposits.

According to Richard Werner (2012), more than 95% of all money created in the US and UK is a direct result of credit creation by banks. When a bank creates credit, it also creates money. Post-Keynesians have been making this argument for more than three decades, though few have listened (e.g., Basil Moore was an early propon- ent) and this view was affirmed by the Bank of England (McLeay, 2014): ‘Whenever a bank makes a loan it simultaneously creates a matching deposit in the borrower’s bank account, thereby creating new money.’

Yet, despite the factual basis of this claim, it has been ignored by neoclassical economists, given their attachment to equilibrium analysis.

Banks are authorized to create credit, ex nihilo (‘out of nothing’) so credit (money) cannot be neutral. In creating credit, a bank creates money that a borrower uses to purchase goods and services that add to aggregate demand and economic growth. Banks are not limited to acting only as intermediaries that move money from savers to borrowers.[4]

Importantly, banks also determine how credit and money are allocated. In the real-world, money creation distinguish-es banks from other financial intermediaries (e.g., shadow banks) that can extend credit but do not possess the ability to create money. Within the financial sector, only banks are granted this authority.

Money is a form of credit, an obligation to pay. In Werner’s (2012) words, ‘banks are the creators of the money supply’ and ‘this is the missing link that causes credit rationing to have macro- economic consequences.’ In short, finance (banking, money and credit) matter!

- Balder, J.M., “Post-crisis perspective: sorting out money and credit and why they matter!”, Real World Econ Rev., issue no 85, 2018. http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue85/Balder85.pdf

-

Keen (2011 and 2017) and Werner (1995, 1997 and 2012).

-

Mainstream economics continues to assert that credit and money are neutral and do not impact real economic activity. Neo- classical economists have good reason to be defensive. Given the structure of their models, dropping the neutral money assumption will result in an indeterminate outcome.

See the original paper by Balder for details of the year-dated references.

Editor’s comments: There is much more that could be written about this subject, but several points relating to the above can be made:

The loanable funds doctrine is an attempt to explain the market interest rate, in which the interest rate is determined by the demand for and supply of loanable funds. The term loanable funds includes all forms of credit, such as loans, bonds, or savings deposits.

Neutrality of money is the false idea that a change in the stock of money affects only nominal variables in the economy such as prices, wages, and exchange rates, with no effect on real variables, like employment, real GDP, and real consumption.

The loanable funds view of interest rates and money neutrality are both properties of general equilibrium models, which are them- selves rooted in a view of money as an addition to a previously barter system.

The words “intermediary” and “intermediation” have more than one meaning. And in particular, bank economists misappropriated and redefined these words to mean some- thing other than their original meaning. Their new interpretation of these words (unlike the interpretation used by Keen and Balder) has been designed to fit comfortably within the orthodox paradigm.

The following sentence is ambiguous and misleading: “Money is a form of credit, an obligation to pay”. It would be closer to the truth to say that bank credit is a form of money. Meaning the entries credited to a payee’s account by a bank whenever it lends or spends, or when a sovereign government net spends or lends. And money is not an obligation to pay; it is an entity which facilitates a payment.

Post-Keynesian economists have been making these arguments for more than three decades, though few have listened to them. The New York Fed explained it in 1969, and people working on the operations side of central banks and in private banks have known it for many years. It is academic (neoclassical) economists who were not interested, as it didn’t fit their agenda.

Werner’s statement that 95% of all money created in the US and UK is a direct result of credit creation by banks is also misleading, because when central governments spend or lend into the real economy, they also create deposit liabilities for banks, which are matched by reserves at the central bank.