Enclosure day? – Colin Cook

Land was the first community asset to be ‘privatised’, taken over for private use and benefit. Way back in the mists of time, long before King Arthur burnt his cakes, long before the British Isles were so named, all land was common land; none was ‘owned’ by anyone but parts used by small family groups for their subsistence. Over centuries in those northern isles, larger, more belligerent groups established areas of exclusive use – and chieftains, warlords and Lords of the Manor declared such areas as ‘my land’. Thus the concept of private property as opposed to the common, or community, land took hold.

Land was the first community asset to be ‘privatised’, taken over for private use and benefit. Way back in the mists of time, long before King Arthur burnt his cakes, long before the British Isles were so named, all land was common land; none was ‘owned’ by anyone but parts used by small family groups for their subsistence. Over centuries in those northern isles, larger, more belligerent groups established areas of exclusive use – and chieftains, warlords and Lords of the Manor declared such areas as ‘my land’. Thus the concept of private property as opposed to the common, or community, land took hold.

As human populations increased and society became more sophisticated, these concepts were codified by Acts of Parliament – copyhold, tenancies, free- hold title, Crown Land – but commons with their age-old rights providing large parts of the population with shelter and

sustenance remained. It should be noted that the commons recognised a form of collective ownership of rights; specified persons only had ‘rights of common’. It was not a free-for-all.

Contrary to the myth of ‘The Tragedy of the Commons’ – as enunciated by W Lloyd in 1833 and promulgated by G Hardin in 1968 – generally commons were well managed by local committees and various courts of manorial juris- diction to provide the ongoing needs of the community; these elemental comm- unities ‘lived’ sustainability and were not just a band of neo-liberal, economic rationalists each seeking maximum personal benefit as Lloyd and Hardin would have us believe.

Enclosure – privatisation of land

The real tragedy of the commons was that vast areas were usurped by innumerable Acts of Enclosure passed by the Parliament at Westminster. These Acts – enacted with skulduggery of every description – made it legal for the large landowners to privatise what had previously been common land used by many of the lower echelons of society in a variety of ways for their subsistence.

Between 1700-1760, 152 Acts allowed the enclosure of 240,000 acres of common fields and waste, between 1761-1801, 1500 acts 2,400,000 acres – in 40 years, 10 times more than in the previous period of 60 years – and between 1802 and 1844, 1,100 acts enclosed 1,600,000 acres (quoted by the Hammonds, figures rounded).

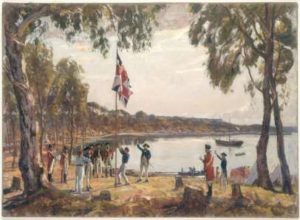

Notice that when white Australia was founded in late 18th century, enclosure activity was at a peak. The founding of white Australia and Acts of Enclosure were very closely connected not just in time but also in the prevailing attitudes.

The UK elite, effecting and benefitting from the enclosures, really only took any notice of those who could make themselves heard; persons of some substance or influence. The illiterate cottager who simply enjoyed the various rights of common that his father enjoyed stood no chance against an Act of Enclosure; dissenters were required to provide written chapter and verse of their rights and argue them in front of Commissioners. Indeed such lowly citizens were barely considered in the deliberations in Westminster. So it is not surprising that when Westminster’s expedition arrived here in 1788, the concept of Enclosure came with them. The idea of commons and persons using the land just for living were of no consequence.

Settlement mind-set

Thus at the beginning of white ‘settlement’ of Australia the ‘Establishment mind-set’ was one of ‘enclosure’ – the concept of ‘commons’, where land is not owned by any but used by many, was in their view out-dated, bad, inefficient, if indeed they thought about it at all. From my understanding, Australia then was like a vast, continent -wide, agglomeration of Aboriginal Commons – the land not ‘owned’ at all but used, shared, nurtured and venerated by the numerous tribes of the indigenous population according to their needs and culture. White man did not see this at all, it was ‘terra nullius’ and the commoners were ‘brushed aside’ with no thought of compensation – much as in England. Henry Reynolds has written of this in his ‘Frontier’ (Allen & Unwin 1996); Dr Reynolds examines the close parallels between the conflicts in Europe and the British settlement of Australia; ‘the Aboriginal experience can be profitably compared to those of squatters on the shrinking commons, the foresters and men of the fens who struggled to maintain a traditional economy in opposition to the ever growing commitment to absolute property rights’.

Tasmania was different

Van Dieman’s Land would seem to be the one place where the concept of ‘the commons’ did flourish for a few years. ‘Van Diemen’s Land was aught but a vast common’ quotes James Boyce, p70, ref32 in his very well researched history, Van Diemans Land (Black Inc. 2008). Ironically, many had been sentenced to transportation because they had been caught out using the commons of England in traditional ways – trapping and snaring game, ways that had been made illegal under the Game laws and Acts of Enclosure. Boyce’s Introduction contains many references to convicts’ acceptance of sharing resources with aborigines and each other – land, water, game – and their adaptability to go bush, to obtain ‘the essentials of life from the new land’. The early chapters contain many specific references to Van Diemans Land as a common and its effect on the early settlers, how the free access to the natural resources led to much entrepreneurial activity and even ideas of independence and democracy. Such moves were stamped out by Governor Arthur to produce a servile population to meet the needs of the increasing number of free settlers on their large land grants.

Aboriginal philosophy

A deeper connection between the idea of commons versus enclosures was brought to mind a year ago at a Fedtalk by Aboriginal academic and activist, Dr Mary Graham, QUT. She spoke about Aboriginal philosophy in comparison to ‘western’ modes of thought saying that aborigines had no difficulty in holding to different concepts simultaneously. In contrast, western views were ‘either or’, ‘this or that’, ‘alive or dead’. This is an exact parallel as between enclosures (this is mine, not anybody else’s) and common land that has many users and uses. This is also shown in the western, legalistic ‘Native Title’ when ‘Aboriginal Common’ would have been more representative of traditional status. Dr Graham’s talk may be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAwBqTVbxNs

This article was published in the Byron Shire ECHO on January 18, 2017 under the headline, ‘Commons: owned by none, used by many’

Colin Cook is an ERA member living in NSW, and is a retired engineer with an interest in researching current and potential monetary systems.

Colin Cook is an ERA member living in NSW, and is a retired engineer with an interest in researching current and potential monetary systems.