Australian housing affordability the worst in 130 years – Philip Soos and Lindsay David

Economists and co-founders of LF Economics, Phillip Soos and Lindsay David, present compelling evidence that our economic system is eating the young alive.

The astronomical bubble in Australian housing prices has generated plenty of commentary regarding the current lack of affordability. This state of affairs clearly concerns aspiring home buyers everywhere, and those living in Sydney and Melbourne in particular.

The astronomical bubble in Australian housing prices has generated plenty of commentary regarding the current lack of affordability. This state of affairs clearly concerns aspiring home buyers everywhere, and those living in Sydney and Melbourne in particular.

First home buyers (FHBs) face almost insurmountable odds: the highest price to income and deposit to income ratios, the lowest savings rates, runaway dwelling prices, weak wage growth, including a political and economic establishment hell-bent on ensuring land prices keep on inflating no matter the wider cost to the economy.

The legion of vested interests – basic- ally 99% of commentators – choose to contend that housing is actually more affordable today than back in the days of high mortgage interest rates, especially when rates peaked at 17% in 1989. This is demonstrated by the standard mortgage payment to household income formula shown below, assuming 80% loan to value ratio (LVR).

Their contention is bogus, however, because the metric is a static one, displaying mortgage payments to income at a particular point in time. The peak in 1989, for instance, is very high if, and only if, prices, interest rates and incomes remain constant over the life of the mortgage. However these variables change by the next period. So, a more dynamic approach is required to assess housing affordability.

The correct method was advocated by Glenn Stevens in 1997, by Guy Debelle in 2004 and other economists like Dean Baker, who identified the U.S. housing bubble and predicted the GFC (Global Financial Crisis) in 2002. The important factor to consider is the effect wage inflation has upon mortgage payments.

While high mortgage interest rates result in large mortgage payments relative to income, this only occurs in the early years of the mortgage as high wage growth inflates away the burden. In contrast, borrowers facing high housing prices with low interest rates and poor wage growth face a greater burden across the life of the mortgage due to greater payments to income.

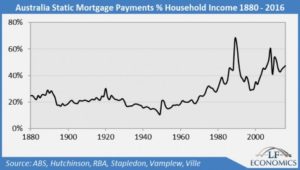

This housing affordability analysis is applied to long-term annual data between 1880 and 2016, anchored to the median house price at an LVR of 80% at the start of each decade there- on. While data on mortgage interest rates and wage growth for the years after 2016 cannot be known, they are assumed to hold still at the present rates: 5.4% for the mortgage interest rate and 1.4% for wages.

The chart below illustrates the outcome of applying this method, demonstrating the proportion of aggregate mortgage payments to household income over the 25 years of the mortgage. The results are overpowering.

Affordability was strained during the 1890s for a long time, primarily due to the decline of household income which stemmed from the collapse in nominal wages during the worst economic depression on record. The persistently high unemployment rate prevented a recovery in wage growth throughout this decade.

The best period for house purchase was between the 1940s and 1970s: regulated social democratic capitalism. These decades were demarked by low housing prices and mortgage interest rates, and high nominal wage growth. The extreme wage explosions in the early 1950s and mid-1970s significantly assisted borrowers by inflating away mortgage payments.

The best period for house purchase was between the 1940s and 1970s: regulated social democratic capitalism. These decades were demarked by low housing prices and mortgage interest rates, and high nominal wage growth. The extreme wage explosions in the early 1950s and mid-1970s significantly assisted borrowers by inflating away mortgage payments.

From the 1980s onward, conditions became more difficult as wage growth declined, interest rates rose and housing prices increased. While the single worst year for purchase would’ve been in 1989, buyers benefitted from declining interest rates and the eventual recovery in wage growth, including the escalation in housing prices from 1996 onward.

The year 2010 stands out above all else. Extreme housing prices combined with the lowest nominal wage growth post-WW2 means mega mortgage mugs will not have their loan payments inflated away, despite lower interest rates than in the decades between 1980 and 2000. The stats for 2017 will be shocking.

There are three ways to assist afford- ability: declining interest rates, rising wage growth and falling housing prices. Presently, the only pathway to improved affordability is the latter option. This is obviously opposed by political parties, the FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate) sector and economists employed by these vested interests.

Trends are ominous for recent and aspiring buyers. Nominal wage growth will continue to decline as economic growth limps along, no productivity- enhancing policies have been enacted in recent times, underemployment continues to rise, the terms of trade will weaken over the long-term and excess- ive immigration floods an already weak labour market.

Nominal rental price growth is currently the weakest since the early 1990s recession, which was the worst economic downturn in post-WW2 history. In some cities such as Perth and Darwin, rents are plummeting. The largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne, are experiencing tepid rental price growth as population inflows mount.

The Treasurer, Scott Morrison, stated that low wage growth was the biggest challenge facing the economy, yet hypocritically continued to attack wages, workers and unions. Worse, given the likelihood of recession over the next 25 years, possibly even GFC 2.0 with a Chinese economic downturn, nominal wage growth could turn negative for the first time since the Great Depression.

Additionally, there are a variety of upwards pressures causing mortgage interest rates to rise, independent of the policy rate. With interest rates and bond yields reflating in some developed countries, Australian banks cannot avoid paying more to fund their operations or they will find it increasingly difficult to raise wholesale funds from international markets.

APRA’s second round of macroprudential controls are giving the banks the excuse to raise rates on interest-only loans, pushing more borrowers to convert to principal and interest mortgages. Both measures produce higher mortgage payments relative to income. With household balance sheets squeezed on all sides, servicing mortgages will become increasingly challenging.

Indeed, it is difficult to see from where high wage and rental price growth will eventuate, and it is highly unlikely that mortgage interest rates can be further reduced significantly.

So where does this leave those young people looking to buy? Simply put, they are up a certain creek without a paddle. With the economy thoroughly anchored to continued growth of private debt, policymakers cannot allow housing prices to fall by any significant measure for the benefit of new buyers.

Source: Renegade Inc., July 2017. Reproduced with permission of the authors. Published originally by Renegade Inc. which is dedicated to everything we got wrong about the economy, business, tech, arts, culture.

Philip Soos is co-founder of LF Economics, co-author of Bubble Economics and an economics PhD candidate investigating Australian bank and mortgage control fraud.

Lindsay David is author of Australia: Boom to Bust, and Print: The Central Bankers Bubble. He recently founded LF Economics and holds an MBA (IMD Business School).

Lindsay David is author of Australia: Boom to Bust, and Print: The Central Bankers Bubble. He recently founded LF Economics and holds an MBA (IMD Business School).