Why the UK can’t afford Rachel Reeves

Steve Keen

The decision to abolish the winter fuel payment is not just bad politics and ethics, but also bad economics

Rachel Reeves, the UK’s new Chancellor of the Exchequer has already coined two phrases that will define her legacy:

1. “If we cannot afford it, we cannot do it” to describe what she thinks the Labour Party cannot do in office; and

2. “The money was not there. A 22billion-pound Black Hole…” to describe what she asserts the Conservative Party left as a legacy for the Labour Party.

Reeves believes that the Labour Government must scrap many of the spending plans of their predecessors and even cancel a universal benefit previously paid to pensioners to help them meet their winter fuel bills to avoid economic catastrophe for the UK. According to Robert Peston, she explained to the Parliamentary Labour Party that these policies were needed to ensure that economic growth occured instead:

“ If we show, as I believe we will, that economic stability is the hallmark of Labour Governments, there is no limit to what we can achieve, because with that stability comes investment. With investment comes growth. With growth comes prosperity. ”

You may be wondering how freezing 4,000 pensioners to death this winter could bring about economic growth.

The explanation can be found in the pages of any economics textbook — and Rachel Reeves has made much of her qualifications in economics: a first PPE degree from Oxford, an MSc in Economics from LSE, and six years working experience at the Bank of England. Reeves is making this ethical mistake because she is applying what she learnt in her economics training. It is also an economic mistake, because the analysis in economics textbooks is simply wrong.

The bad economics of cutting government spending

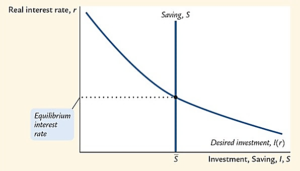

The argument that cutting government spending will lead to a rise in private investment is made in the very first mathematical model in the influential textbook Macroeconomics, by Gregory Mankiw (Mankiw 2016). This is the model of “the market for Loanable Funds”, which is how mainstream economists model money. The model is shown as a pair of intersecting supply and demand curves; as Mankiw notes, “saving and investment can be interpreted in terms of supply and demand. In this case, the ‘good’ is loanable funds, and its ‘price’ is the interest rate. (p 72). See Figure 1.

In this model, the supply of savings is shown as fixed. Mankiw also assumes that the output of goods and services is fixed.

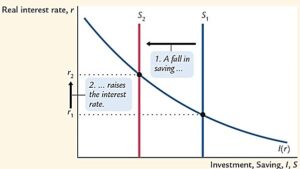

Mankiw then asks what happens if there is an increase in government spending. The answer is that an increase in government spending causes an identical fall in the level of investment, by taking some of savings away from the private sector.

His argument is that this leads to less investment, and a higher interest rate. See Figure 2.

Mankiw’s explanation asserts that increased government spending reduces investment:

“Consider first the effects of an increase in government purchases… The immediate impact is to increase the demand for goods and services… But because total output is fixed by the factors of production, the increase in government purchases must be met by a decrease in some other category of demand. Disposable income … is unchanged, so consumption … is unchanged as well. Therefore, the increase in government purchases must be met by an equal decrease in investment. To induce investment to fall, the interest rate must rise.

Hence, the increase in government purchases causes the interest rate to increase and investment to decrease. Government purchases are said to crowd out investment.” (p73, italics emphasis added; omitted from this quote are some algebraic symbols)

Reeves is simply reversing this argument, to assert that a reduction in government spending will lead to a rise in investment.

There’s just one problem with this argument: it’s baloney, because “the market for loanable funds” doesn’t exist. And you don’t have to take my word for it: you can take the word of Michael Kumhof, who is the Senior Research Advisor to Reeves’ former employer, the Bank of England.

In a paper entitled “Banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds — and why this matters” (Kumhof and Jakab 2015), it is explained that this model is a myth. In fact, the entire mainstream theory of commercial banking is wrong.

Since she’s following a false theory, Reeves’ policies will have the opposite effect to what she intends: cutting government spending will reduce the supply of money, and reduce investment, rather than increase it.

To understand why this is so, you have to understand how banks work – and economics textbooks are simply wrong about this, as another paper by Reeves’ ex-employer confirms. Entitled “Money creation in the modern economy”, it states that:

“The reality of how money is created today differs from the description found in some economics textbooks.” (McLeay, Radia, and Thomas 2014)

Therefore, if you’ve uncritically accepted what you’ve been taught in economics textbooks about how money is created, you have been misled. That is the situation for Reeves, and it’s why she’s doing bad things with the best of intentions.

Elsewhere I have also explained why Reeves’ policies are destined to backfire, and actually reduce rather than increase economic development.

Source: Steve Keen from Building a New Economics [email protected]

Prof Steve Keen is Distinguished Research Fellow at the Institute for Strategy Resilience & Security, University College London, and is an ERA patron. If you like Steve’s economic analysis then you are invited to support his work by signing up to either of the following networks:

(a) Patreon

(https://www.patreon.com/ProfSteveKeen – minimum $10 per year);

(b) Substack

(https://profstevekeen.substack.com/ -minimum $5 per month).