A green job guarantee

Steven Hail

The be all and end all of most macro- economic debate in recent years – recent decades, really – has been GDP (strictly speaking, ‘real GDP’, or ‘GDP at constant prices’, or inflation- adjusted GDP). Whilst some attempt is made to adjust these statistics over time for changes in product quality, it remains the case that GDP statistics are essentially about quantity. When we discuss ‘economic growth’ with reference to GDP data, we are implicitly assuming that

The be all and end all of most macro- economic debate in recent years – recent decades, really – has been GDP (strictly speaking, ‘real GDP’, or ‘GDP at constant prices’, or inflation- adjusted GDP). Whilst some attempt is made to adjust these statistics over time for changes in product quality, it remains the case that GDP statistics are essentially about quantity. When we discuss ‘economic growth’ with reference to GDP data, we are implicitly assuming that

- More is always best.

- Ever increasing volumes of product- ion are necessarily desirable.

- Ever increasing volumes of product- ion are ecologically feasible.

- More physical goods and services always imply higher aggregate social well-being.The first point to be made here is that there is virtually no evidence, for those countries with a GDP per capita of about the level of Portugal or above,

that ‘economic growth’ implies higher social well-being. The Easterlin Paradox, as it has been known since the mid-1970s, refers to the fact that significant links between rising real GDP per head and rising reported well-being are difficult if not impossible to discern. More things do not seem to bring happiness.

Moreover, social researchers like Richard Wilkinson have shown that the most successful societies, by a wide variety of metrics, are not those with the higher per capita GDPs.

Whether you study measures of health, including mental health, social problems such as crime, or access to public services like education, a higher GDP does not seem to help much, if at all. Measures of inequality tell you far more about the success of a society than the GDP statistic.

Furthermore, it does not appear to be the case that inequality of income is a central problem in these societies – people are at least if not more concerned with relative social status and feelings of self-esteem and societal respect than they are with relative financial deprivation. The issue of involuntary unemployment is of vital importance. Keynes, Kalecki, Minsky and other far-sighted economists always placed more emphasis on full employment, and on the eradication of involuntary unemployment, than they did on any measure of national output.

Today, we have another and more compelling reason to emphasise employment and to shift away from maximising GDP growth as a policy objective. This new reason is that there may be no such thing as ‘sustainable growth’ in Real GDP in the future – and whether or not you accept that, there must be some level of GDP growth which is the maximum that is ecologically sustainable. Either we will have to transition to a steady state economy (with no further net growth in output), or we will at the very least have to moderate our growth, and to modify both what we produce and how we go about producing those goods and services we will consume in the future.

Some ecological economists, such as Assoc Prof Phil Lawn of Flinders University, argue that we are already using up the scarce ecological resources of our planet in an unsustainable way. Given our use of non-renewable natural resources, and our emissions of waste products at a rate higher than the planet can assimilate without a deteriorating environment, they argue we are already producing too much, and may need to shrink the world economy (reduce global GDP) to maintain anything approximating to our current life-styles in future generations.

Other modern money theorists, like Prof Bill Mitchell of Charles Darwin University and the Centre of full Employment and Equity (University of Newcastle) take a more optimistic view. They argue that changes in what we consume and how we produce it, combined with advances in technology (for example, in energy production) and in recycling, may permit some economic growth into the foreseeable future – albeit not at the same rate that would be necessary for an entrepreneurial private sector, using modern technology, to absorb the available labour force. Whichever of these camps you fall into, it remains true that

- Given ecological constraints and likely technological changes, it is likely that the demand for labour in the private sector will contract in the coming decades.

- In the past, economic growth has eventually absorbed those workers who have been replaced by labour saving technology

- In the future, such economic growth may not be ecologically feasible

- In the absence of a job guarantee, this implies deteriorating job prospects for all except the most highly educated, and the development of levels of inequality which will under- mine social stability.Phil Lawn gave a presentation at a conference at the University of Newcastle in late 2013, where he explored the potential for ‘Keynesian full employment’ GDP to be above ‘ecologically sustainable’ GDP. The traditional Keynesian definition of full employment GDP would be the level to which ‘pump priming’ demand management (lower interest rates and deficit spending/tax cuts) could increase the demand for labour in the private sector without creating rising inflationary pressures.

If this is above that level of output which is consistent with the ‘carrying capacity’ of Planet Earth, then there is no way that a traditional Keynesian stimulus can be relied upon to maintain equitable full employment without putting our ecosystem in peril.

It must then be the role of a “Green Job Guarantee” to pull the full employment GDP back down to equal the ecologically feasible GDP. Saving the planet might mean not creating enough jobs in the private sector to maintain acceptable levels of employment and equality. The only solution to this problem which is consistent with the maintenance of a stable and successful society is a ‘Green Job Guarantee’, as advocated by Bill Mitchell, the American economist Matt Forstater, Phil Lawn and an increasing number of other visionaries.

Without a Job Guarantee, the objectives and policies of the Greens – not just in Australia, but worldwide — may not add up, and perhaps cannot be made to add up. Both a Job Guarantee and a thorough understanding of and advocacy of the principles of public finance viewed through a modern monetary theory lens are essential. We can’t save the world without these ideas.

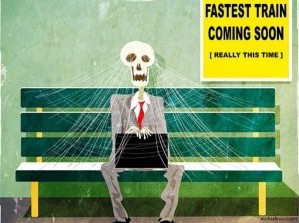

Modern monetary theorists and advocates of a job guarantee are still hoping for progressive politicians to examine these proposals seriously, with a view to making them part of a vision for a sustainable and equitable economy. A good start would be to consult some of the extensive research into the administrative challenges of implementing an effective job guarantee in Australia done by Bill Mitchell and his colleagues in recent years.

Steven Hail is adjunct lecturer in economics at Adelaide University, with special interests in financial economics and heterodox macroeconomics, and is an ERA member.