Understatement of unemployment

John Haly

In Australia, the media and government utilise Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) unemployment statistics. These indicate that the jobless rate has been rising since late 2022 after a post-pandemic decline. I am not referring to percentages, which are a function of the total labour force (also trending upwards), but rather to “real” numbers. Still, I have to query the authenticity of these figures. National unemployment metric methodology seldom characterises unemployment as individuals without compensated employment or those unable to secure jobs. Instead, the methodology restricts or omits various groups of the unemployed from being included in the count.

The orthodox economic model posits that unemployment is influenced by supply and demand dynamics, where “supply” refers to workers seeking employment who possess a reservation wage that they are prepared to accept. This is absurd considering the desperation for employment among many. ABS, methodology incorporates active job searching and the absence of gig employment to qualify as unemployed. Unavailability, because of earlier responsibilities, any association with a gig role (regardless of compensation), or lack of proof of a current job search during the past month results in exclusion from ABS figures.

The official unemployment measure is entirely arbitrary and constrained by an institutional structure. The individuals included in the count are strictly determined by a nation’s specific interpretation of a series of methodological guidelines. This may adhere closely or loosely to the regulations established by the International Labour Organisation [Sorrentino, 2000]. Each shift or deviation of the methodology specific to a nation, garners different results. For instance, limiting the active job searches to the past four weeks yields a particular unemployment rate. Extending the timeframe to five or six weeks produces a likely different number. In Europe, the unemployment definition specifies an unemployed person as one currently available for work in the next fortnight, as opposed to the “immediate” availability for work requirement set by Australia’s ABS [Eurostat, 2010]. This results in a variation in the unemployment rate. The rate a country selects is solely determined by the prescribed regulations and the class for whom those guidelines are established. The unemployment rate is based on the cut-off specified within the methodology and the demographic it is intended to serve. “For whom the bell tolls” (to cite John Donne) is significant — and the bell tolls for class divisions in Australia.

The ABS, in particular, rings its bell for the capitalist class.

By “capitalist class,” I refer to the Veblen Institutionalist’s subdivision of the traditional Marxian ruling class. This includes enterprise owners and managers whose income is derived from profits, on accumulating capital through asset ownership and who predominantly own the means of production [Pluta & Leathers, 1978, p128]. The statistic’s main domestic use is to assess the unimpeded access to the working class by the capitalist class. It is imperative to understand that ABS statistics do not represent individuals without compensated employment or those unable to secure jobs. The exclusions by the ABS make this very evident. I will substantiate my argument by looking at the ABS methodology some of which is provided in their 2023 online publications [ABS, 2023].

1. The ABS data excludes individuals unable to commence immediate employment. As highlighted in Gareth Hutchens’s articles in the ABC, excludes thousands of unemployed individuals [Hutchens, 2021].

2. Exclusions for uncompensated labour in a familial enterprise, busking or street vending. Why? Due to your engagement in other demanding tasks, you may not be instantly accessible to the Capitalist Class.

3. Excluding individuals participating in the government unemployment programs such as the PaTH initiative. Why? It is necessary to exit such programs prior to embarking in properly compensated labour for the Capitalist Class.

4. Excluding Australians employed for zero hours due to ‘economic reasons’ yet maintaining a gig attachment.

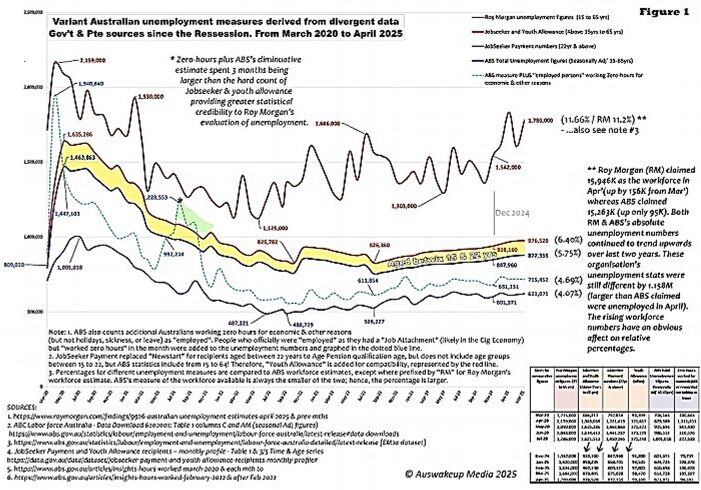

Why? Being committed to a “job attachment” (as termed by the ABS), which is fully unpaid due to the absence of employment provided, serves as an obstacle to the exploitation by the Capitalist Class [ABS, 2021]. By the conclusion of 2024, the estimated figures were projected to range from 80,000 to 90,000, while in 2020, the numbers fluctuated between 200,000 and over one million individuals. (see Figure 1)

5. Excluding unemployed individuals lacking evidence of actively seeking employment due to familial, personal, or other obligations. Why? To prevent distraction from the Capitalist Class’s request for their engagement.

6. Exclusions of transient foreign individuals in the country pursuant to the 12/16 regulation [ABS, 2023] . Why? Lack of acquaintance with the culture, work, and social environment can hinder fully assimilated employment engagement by the Capitalist Class.

7. Excluding those who have been employed by any other entity for over one hour within a month. Why? During the designated “reference week” or the four weeks preceding its end, you were not available for exclusive employment by anyone in the capitalist class.

8. Excluding anyone over the age of 65, regardless of their active job seeking status. Why? Your age, physical ability, and other factors may restrict your potential for complete exploitation by the capitalist class. We live in an ageist society that dismisses individuals long before they reach 65, regardless of their experience or abilities.

ABS measures represent an arbitrary subset of the labour force that is not only unemployed lacking in any source of income, (outside of government welfare or family support) and also subject to a list of exclusions. This sub-group is characterised by age limits, active job-seeking behaviour, immediate availability, absence of distractions, and no potential impediment to engagement in capitalist exploitation whatsoever at any interval of time longer than an hour in four weeks. That is a rather limited subset.

Its size is consistently half to one-third smaller than the actual count of individuals to whom the Australian government disburses welfare for unemployment (Jobseeker). I should additionally declare that the number of individuals compensated by Jobseeker has also increased since mid-2023.

When encountering media and politicians’ statements, such as those of Jim Chalmers and members of the Labor cabinet, in multiple Twitter messages, “unemployment is low” as indeed is so reported by the ABS, I would argue that this is entirely misleading. When reiterating that absurdity, reflect on the agenda and propaganda of the capitalist and ruling class. Irrespective of whether it is done intentionally, naively, consciously, or otherwise, it is misleading. It also had consequences, such as influencing the RBA to raise interest rates (Haly, 2024). What is a more accurate depiction of unemployment? Is there data that provides a more accurate assessment of individuals without compensated employment or those unable to secure jobs?

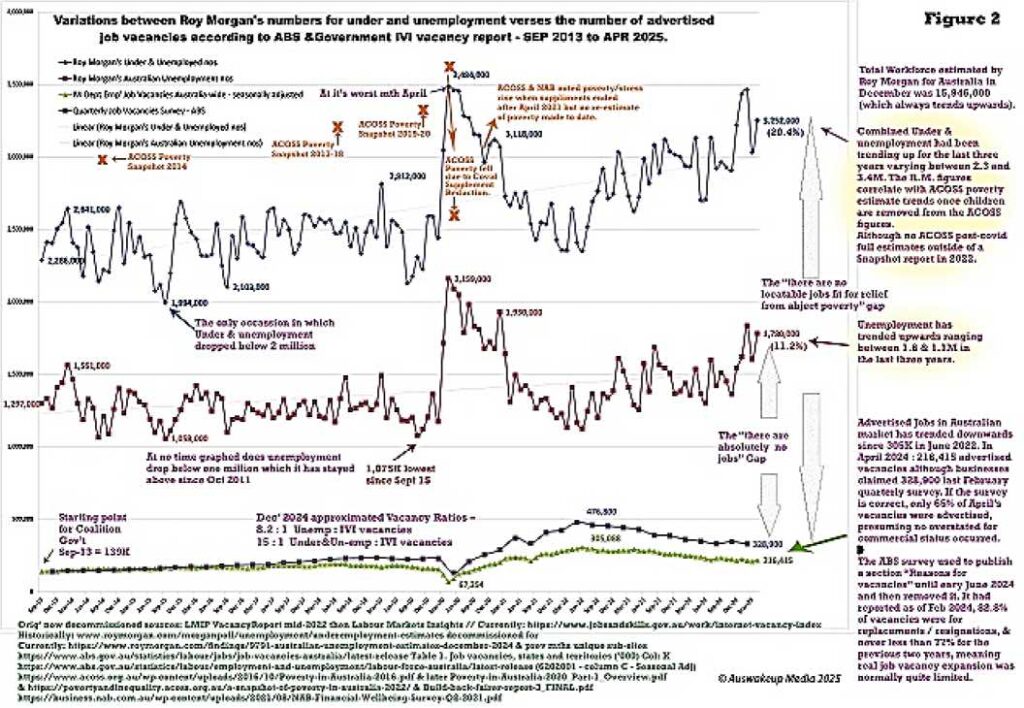

Examine the results of Roy Morgan’s methodology presented in Figure 2 and note its relative alignment to past poverty measures by ACOSS. Especially given, for example, the average relative size of the first 4 months of 2025 for ABS’s measurement of combined unemployment and underemployment numbers is 45% of Roy Morgan’s numbers. Roy Morgan suggests that the unemployment rate in Australia has been in double digits all of 2025 to date (above 11% in April), and the combined unemployment and underemployment rate, with one exception (March @ 19.3%), has been above 20%. ABS, Jobseeker payments and Roy Morgan indicate that unemployment has consistently grown since late 2023, if not as early as late 2022. With all that, what is a more accurate representation of our societal unemployment state?

Examine Figure 2’s two measures of job vacancies, which, although having their own issues with arbitrary measurement, originate from distinct governmental sources and methodologies (Tan, 2025). Examine the disparity between existing vacant positions and the number of people who are either unemployed or unable to secure adequate employment.

In the lead up to the recent election, such perspectives were politically undesirable, particularly as progressive pundits sought to prevent a resurgence of what they believed were dysfunctional ultra-conservative governments, especially with any affiliations to the Trump Presidency. The present government may have demonstrated greater stability than the preceding decade, which had been marked by dysfunction, corruption, and scandals under the Liberals (Seccombe, 2023). Still, it remains less than optimal. Unemployment has not improved, no matter what methodology one prefers to quote, and the government must enhance its efforts. I would advocate for a “Federal Job Guarantee”; nonetheless, it will likely face vehement opposition from the capitalist class (Hail, 2021). We should advocate for Full Employment policies reminiscent of the ones that resulted in less than 2% unemployment for 25 years following Prime Minister John Curtin’s initiative, but minimally, we must dismiss corporate and political rhetoric, no matter our political affiliations, that claims Australia has low unemployment (Knox-Haly & Haly, 2024).

John Haly is a postgraduate student of Torrens University (Master of Economics of Sustainability)

References

1. ABS. (2021, November 11). Insights into job attachment during the pandemic. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au website: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/insights-job-attachment-during-pandemic

2. ABS. (2023, November 24). Australian Labour Account. Retrieved from www.abs.gov.au website: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/detailed-methodology-information/concepts-sources-methods/labour-statistics-concepts-sources-and-methods/2023/methods-four-pillars-labour-statistics/australian-labour-account

3. Eurostat. (2010). Glossary:Unemployment – Statistics Explained. Retrieved from Europa.eu website: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.

php?title=Glossary:Unemployment

4. Hail, S. (2021). The Return of Full Employment – Steven Hail. Retrieved May 18, 2025, from Australian Fabians website: https://www.fabians.org.au/afr2_steven_hail

5. Haly, J. (2024, January 9). When it comes to unemployment, the RBA has got it wrong. Retrieved from Independent Australia website: https://independentaustralia.net/politics/ politics-display/when-it-comes-to-unemployment-the-rba-has-got-it-wrong,18225

6. Hutchens, G. (2021, October 16). Why are millions of unemployed people excluded from our monthly “unemployment” data?. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/ news/2021-10-17/why-are-millions-of-unemployed-people-excluded-from-the-data/100543854

7. Knox-Haly, Dr. M., & Haly, J. (2024, March 13). Positing Job Guarantee Antecedents -Part 1 of 2. Retrieved from WEA Pedagogy Blog website: https://weapedagogy.wordpress. com/2024/03/13/positing-job-guarantee-antecedents-part-1-of-2/

8. Pluta, J. E., & Leathers, C. G. (1978). Veblen and Modern Radical Economics. Journal of Economic Issues, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.1978.11503508

9. Seccombe, M. (2023, March 18). A brief history of Liberal Party scandals. Retrieved from https://www.thesaturdaypaper.com.au/news/politics/2023/03/18/brief-history-liberal-party-scandals

10. Sorrentino, C. (2000, June). International unemployment rates: how comparable are they? Retrieved from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics website: https://www.bls.gov/opub/ mlr/2000/06/art1full.pdf

11. Tan, J. (2025). How Useful are “Leading” Labour Market Indicators at Forecasting the Unemployment Rate? | Bulletin – April 2025. Reserve Bank of Australia, (April). Retrieved from https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2025/apr/how-useful-are-leading-labour-market-indicators-at-forecasting-the-unemployment-rate.html