Revising Adam Smith – J.D. Alt

The Ebook Diagrams & Dollars (in the top 10 bestsellers on Amazon/ category money & monetary policy) paints an optimistic picture of what “Sovereign Spending” could achieve for our collective benefit. The video made from it (approaching 3,000 views on You Tube – thanks Haiku Charlatan) ends with cheering calisthenics around the final diagram of our national prosperity. Unfortunately, the “real world” of our Congressional leaders and media spin-machine is painting a very different picture – a dire vision of out-of-control government spending and national insolvency. Understanding why that is, and what we can do about it, is the real challenge we have before us.

There have been some notable moments in American history when effective Sovereign Spending seems to have been accomplished: Rural electrification, the Interstate Highway system, the Man-to-the-Moon and Space Shuttle programs come to mind. And then, of course, there was the unprecedented command economy collectively created to win World War II – a coordinated effort which saw U.S. Sovereign Spending invent, usher in, or lay the groundwork for virtually every technological breakthrough of our contemporary world.

For the most part, however, the ability of our political system to allocate and manage Sovereign Spending has been, and continues to be, pathetically short on results. Our most recent efforts – the “Stimulus”, Hurricane Sandy rebuilding, and Obamacare – could reasonably be considered exercises in futility. Why is it such a struggle to do good things for ourselves?

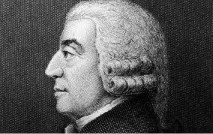

Part of the reason has got to be the resilient stranglehold Adam Smith and his seminal book “The Wealth of Nations” continues to wield upon our collective imaginations. His words, more than any I’m aware of, lie at the heart of our collective confusion and dysfunction when it comes to allocating – and then spending – our national budgets. Listen to what he says: “As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other eases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it.”

In other words, our collective good is most effectively produced and maximized when each individual strives exclusively to maximize his own benefit or profit. Furthermore, conscious efforts directed toward producing collective benefits are often counterproductive.

These premises have been joined to become the mantra of Free Market Theology: Any and every effort to “control” the selfish pursuit of private profit (a) diminishes our collective good, (b) intrudes on our individual liberty, and (c) interferes with the “invisible hand” that allocates resources in the most efficient and effective manner.

It is easy to see how this Free Market mantra is an “invisible hand” in its own right, framing and guiding our political democracy on many fronts and levels – from gun-control to pipe-line building to charter schools – however its most challenging difficulty is the cognitive dissonance it creates about Sovereign Spending itself. Specifically, how can we imagine “paying ourselves to create collective goods and services” – as is so effortlessly visualized in Diagrams & Dollars – if individuals are supposed to be employing their own capital to maximize their own benefit and profit?

From this perspective, Sovereign Spending is somehow unnatural — especially when we imagine what is being “spent” are Dollars the government has simply “printed”! If we can’t frame the whole operation so money flows through the hands of private contractors who will then use it to pursue their own self-interest and profit (thereby maximizing the collective good) then we simply cannot bring ourselves to spend it at all, because to do so would be (a) wasteful (b) counterproductive and (c) an intrusion of “big government” on individual liberty.

The problem, of course, is that Adam Smith’s insight, as far as it goes, is basically correct: we can’t argue for Sovereign Spending on the basis that individual initiative and entrepreneur- ship are not or should not be the driving force of our economy. The harder that people work to better 77and benefit them-selves, the better off – in aggregate – we’ll all be. But it ought to be easy enough to show that Adam Smith’s invisible hand actually operates most powerfully and effectively within a collective structure consciously designed and built with Sovereign Spending. In other words, properly conceived, Sovereign Spending doesn’t displace private initiative, it enables and leverages it to higher levels of achievement.

This is so easy to demonstrate, it’s almost a cliché. Take for example a private individual who wants to generate profits for himself by creating and providing a service that helps people find restaurants.

Twenty years ago that individual might have started a yellow-pages type publication that was distributed for free – enabling the selling of advertising space to restaurants. The efficiency and income potential of this business model was, in hindsight, quite limited. Jump forward twenty years and this same individual is able to operate within a newly built collective structure dramatically leveraging opportunities: Now one can create a smartphone App that uses GPS to locate restaurants on a digital map in the palm of a hungry person’s hand. The GPS system, as everyone knows, was created – and is maintained – almost exclusively with Sovereign Spending. The smartphone – as revealed in Marianna Mazzucato’s insightful book, “The Entrepreneurial State” – was also the end result of a long string of technological innovation and development that was paid for not by Steve Jobs’ investors, but by Sovereign U.S. spending.

In light of this new point of view, I would like to take the liberty of rewriting Adam Smith’s critical passage, adding in the sentences necessary to make it a more complete prescription for building the wealth of nations. I hope he won’t mind; and I believe, in fact, that he might even thank me:

“As every individual, therefore, endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other eases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.

Yet it is also apparent his endeavours are greatly eased and facilitated when his labours take place within a collective structure that renders his efforts more effective and productive, and which further enhances his own skills and abilities to undertake them. It is also apparent that it is not in the selfish interest of any one individual to devise and build such a collective structure, and so without a collective effort, it would never be built; and as a consequence each man’s labours would produce only those revenues as can be scratched out in his own isolation. It is evident, therefore, that the annual revenue of a society is rendered greatest when the individuals within that society first employ their sovereign capital to create a collective structure, and then direct their private capital to its greatest value within that enabling and supportive edifice. Without thus proceeding, and by constantly giving short-shrift to the collective goods of society, the invisible hand of self-interest can succeed only in constructing, ultimately, a sociopathic world of conflict and misery.”

Having revised Adam Smith’s critical quotation, we should also update the Free Market mantra that derives from it: Every effort should now be made to devise and build collective structures which enable and enhance the efforts of every individual to exercise his personal liberty to maximize his own benefit and profit without harming the public good; furthermore, any effort to stifle the creation of these collective goods with claims they interfere with private liberty and personal gain shall be understood for what it actually is: a misanthropic myopia that can only result in the aggrandizement of a few at the expense of the many.

If this is now resolved, it leaves us finally with two basic issues to confront:

(1) How can we most effectively determine the goals of our Sovereign Spending? And (2) how can we most effectively guard against the corruption that will inevitably attempt to divert and corral the flow of Dollars?

Source: http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/02/revising-adam-smith.html

J.D. Alt is an architect and author in Annapolis, Maryland. He became interested in understanding – and explaining – Modern Monetary Theory in 2011 while researching a strategy for implementing affordable housing on a national scale. His novel, The Architect Who Couldn’t Sing, won the 2012 eLit Gold Award for architecture. He is a frequent contributor to New Economic Perspectives.