Greece, Germany and the Eurozone

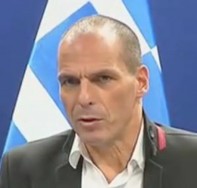

The thoughts of Yanis Varoufakis, extracted from a recent speech

This material has been extracted from the longer transcript of a keynote speech by the Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, delivered at an event of the Hans Böckler Stiftung and the Humboldt-Viadrina Governance Platform in Berlin on 8th June 2015. It was first published on Yanis Varoufakis’ Blogsite.

The alternative news networks have been alive with stories about how the Greek economic crisis – which is really at its heart a European economic crisis – is likely to work itself out.

The following extract from a longer paper by Varoufakis reveals some of his thoughts relating to this issue [Ed].

Divided By A Common Currency

Since the end of the war Greeks and Germans, together with other Europeans, have been uniting. We were uniting despite different languages, diverse cultures, distinctive temperaments. In the process of coming together, we were discovering, with great joy, that there are fewer differences between our nations than the differences observed within our nations.

Then came the global financial disaster of 2008 and, a year or two later, European peoples, who were hitherto uniting so splendidly, ended up increasingly divided by a … common currency – a paradox that would have been delightful if only it were not so fraught with danger. Danger for our peoples. Danger for our future. Danger for the idea of a shared European prosperity.

History does seem to have a flair for farce, judging by the way it sometimes repeats itself. The Cold War began not in Berlin but in December 1944 in the streets of Athens. The Euro Crisis also started life in Athens, in 2010, triggered off by Greece’s debt problems. Greece was, by a twist of fate, the birthplace of both the Cold War and the Euro Crisis. But the causes run much wider, spanning the whole of our continent.

What were the causes of the Euro Crisis? News media and politicians love simple stories. Like Hollywood, they adore morality tales featuring villains and victims. Aesop’s fable of the Ant and the Grasshopper proved an instant hit. From 2010 onwards the story goes something like this: The Greek grass- hoppers did not do their homework and their debt-fuelled summer one day ended abruptly. The ants were then called upon to bail them out. Now, the German people are being told, the Greek grasshoppers do not want to pay their debt back. They want another bout of loose living, more fun in the sun, and another bailout so that they can finance it.

It is a powerful story. A story under- pinning the tough stance that many advocate against the Greeks, against our government. The problem is that it is a misleading story. A story that casts a long shadow on the truth. An allegory that is turning one proud nation against another. With losers everywhere.

Except perhaps the enemies of Europe and of democracy who are having a field day.

Recycling In A Monetary Union

Let me state a truism: One person’s debt is another’s asset. Similarly, one nation’s deficit is another’s surplus. When one nation, or region, is more industrialised than another; when it produces most of the high value added tradable goods while the other concentrates on low yield, low value-added non-tradables; the asymmetry is entrenched. Think not just Greece in relation to Germany. Think also East Germany in relation to West Germany, Missouri in relation to neighbouring Texas, North England in relation to the Greater London area – all cases of trade imbalances with impressive staying power.

A freely moving exchange rate, as that between Japan and Brazil, helps keep the imbalances in check, at the expense of volatility. But when we fix the exchange rate, to give more certainty to business (or, even more powerfully, when we introduce a common currency), something else happens: banks begin to magnify the surpluses and the deficits. They inflate the imbalances and make them more dangerous. Automatically. Without asking voters or Parliaments. Without even the government of the land taking notice. It is what I refer to as toxic debt and surplus recycling. By the banks.

Toxic Recycling

It is easy to see how this happens: A German trade surplus over Greece generates a transfer of euros from Greece to Germany. By definition!

This is precisely what was happening during the good ol’ times – before the crisis. Euros earned by German companies in Greece, and elsewhere in the Periphery, amassed in the Frankfurt banks. This money increased Germany’s money supply lowering the price of money. And what is the price of money? The interest rate! This is why interest rates in Germany were so low relative to other Eurozone member- states.

Suddenly, the Northern banks had a reason to lend their reserves back to the Greeks, to the Irish, to the Spanish – to nations where the interest rate was considerably higher as capital is always scarcer in a monetary union’s deficit regions.

And so it was that a tsunami of debt flowed from Frankfurt, from the Netherlands, from Paris – to Athens, to Dublin, to Madrid, unconcerned by the prospect of a drachma or lira devaluation, as we all share the euro, and lured by the fantasy of riskless risk; a fantasy that had been sown in Wall Street where financialisation reared its ugly head.

Put differently, debt flows to places like Greece were the other side of the coin of Germany’s trade surpluses. Greece’s and Ireland’s debt to German private banks maintained German exports to Greece and Ireland. This is similar to buying a car from a dealer who also provides you with a loan so that you can afford the car. Vendor-finance, is the term used.

Can you see the problem? To maintain a nation’s trade surpluses within a monetary union the banking system must pile up increasing debts upon the deficit nations. Yes, the Greek state was an irresponsible borrower. But, ladies and gentlemen, for every irresponsible borrower there corresponds an irresponsible lender. Take Ireland or Spain and contrast it with Greece. Their governments, unlike ours, were not irresponsible. But then the Irish and Spanish private sectors ended up taking up the extra debt that their government did not. Total debt in the Periphery was the reflection of the surpluses of the Northern, surplus nations.

This is why there is no profit to be had from thinking about debt in moral terms. We built an asymmetrical monetary union with rules that guaranteed the generation of unsustainable debt. This is how we built it. We are all responsible for it. Jointly. Collectively. As Europeans. And we are all responsible for fixing it. Collectively. As Europeans. Without pointing fingers at one another. Without recriminations.

Before 2009 the Greek media were ever so proud that Greece was growing faster than Germany. They were wrong. It was Ponzi, pyramidic, debt-fuelled growth. When our bubbles burst, the German press accused the Periphery of profligacy and of being bad European citizens who got what they deserved. It was the turn of the German press to get it wrong. The Periphery’s exorbitant debts were essential for the industrial machinery and the banking systems of Germany and France to prosper given the problematic bank-based recycling system that we had.

In summary, our Eurozone’s surpluses recycling was at the heart of the problem. Greece and Ireland took a big hit on behalf of a Eurozone that was not designed well. We took a hit to save the banks that did all the recycling so badly. To save a Eurozone economically incapable of absorbing the shockwaves of the large financial crisis that its design had brought on and politically unwilling to re-design our surplus recycling mechanism.

For five years now, Europe and three different Greek governments have been pretending that they solved the crisis while extending it into the future.

Pretending that the nation’s bankruptcy can be dealt with by ever increasing loans on conditions of further income- sapping austerity that undercuts the nation’s capacity to repay. Meanwhile, a Great Depression has taken hold, the political centre has imploded, children faint at school from malnutrition and Nazis are coming out of the woodwork.

As I already said: It is truly pointless to play the blame game. Whose fault was the crisis? We are all at fault. We created a Eurozone with a surplus recycling mechanism which with mathematical precision led to a crisis with victims everywhere. The longer we take to realise this the greater our collective fault.

Read the entire paper by Yanis Varoufakis on either of the following alternative sites:

- Social Europe, 11 June 2015 http://www.socialeurope.eu/2015/06/greece-germany-and-the-eurozone/

-

Yanis Varoufakis Blogsite http://yanisvaroufakis.eu/2015/06/09/greeces-future-in-the-eurozone-keynote-at-the-hans-bockler-stiftung-berlin-8th-june-2015/

Comments from Dennis Dorney: The European trading bloc is now at a crossroads. If it fails and the Euro- zone economy crashes it could bring back the 2008 recession without having successfully resolved it in the time since then. The consequences are likely to be even worse now than then. In short we can hardly ignore it. There are many opinions available on the internet claiming to explain what the issues are in the stand-off between Greece and the Euro-zone, allocating blame etc and mostly placing Greece in the role of villain, but I have never yet seen an article stating what the position of Greece really is, by someone who should know. This article by Varoufakis explains their position clearly and, further, seems to show that the Syriza government has a clearer grasp on the economic realities than those European leaders pushing the austerity model.