Globally, 40% of people won’t have access to clean water by 2030 – Reynard Loki

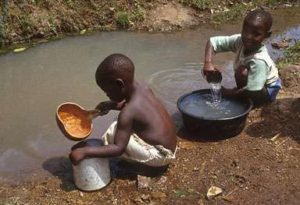

For millions of people across the world, access to clean water so they can drink, cook and wash, is a daily struggle. In many rural, impoverished communities, fetching water is an arduous task that falls upon women and children.

In Africa and Asia, women and children must walk 3.7 miles on average to get their water. Collectively, women spend over 200 million hours every day just collecting water. That’s more than just a major inconvenience, it’s an incredible amount of lost economic potential.

This time-consuming and physically exhausting endeavour prevents women from working at paid jobs and keeps children away from school, impacts that continue a cycle of poverty and socio-economic exclusion. For the women and children who live in a small village in Kenya, their walk to water is more than five miles. And the water they gather isn’t even clean; it comes from a dirty river containing harmful bacteria.

These villagers are not alone. Around 783 million people – 11 percent of the world’s population – don’t have access to clean water, which can be deadly. Lack of clean water and sanitation is the ultimate cause of approximately 3.5 million deaths every year.

It’s a major crisis that could become even worse if nations don’t fully address it soon. Water – being a finite natural resource – is getting scarcer as the global population steadily increases. By 2030, only 60 percent of humanity’s demand for water will be met by existing resources at the current rate of use, according to the U.N. That means four out of 10 people will be without access to water.

“I’ve met people in a number of different countries who are impacted by the water crisis,” said Matt Damon, who is the co-founder of Water.org, a charity that helps communities design and construct sustainable water supply systems.

In a video interview, the actor and activist described a trip to Ethiopia where he watched children retrieve water from a hand-dug well he described as a “filthy hole”. “The water looked like chocolate milk” he said. “They were aware of the dangers of drinking that water, but they just didn’t have a choice.”

It was a long time coming, but finally, in 2010, the United Nations General Assembly recognized that water and sanitation should be basic human rights. “Safe drinking water and adequate sanitation are crucial for poverty reduction, crucial for sustain- able development and crucial for achieving any and every one of the Millennium Development Goals,” said U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon.

In addition, improved water and sanitation can help fight hunger, achieve universal primary education, promote gender equality and empower women, reduce child mortality, improve maternal health, reduce the impact of climate change, protect biodiversity, prevent regional conflict and combat a wide range of diseases, including malaria and HIV/AIDS.

There has been progress. Between 1990 and 2015, 2.6 billion people gained access to improved drinking water sources. Much of that progress was due to nations meeting the U.N.’s Millennium Development Goals.

Notably, the MDGs’ target of halving the proportion of people without access to improved sources of water was met five years ahead of schedule.

But despite these impressive gains, 2.4 billion people are still using unimproved sanitation facilities, including 946 million people who are still practicing open defecation. India still has the highest number, around 190 million people, practicing open defecation, mostly in rural areas. This has led to a number of health impacts, including typhoid, cholera, hepatitis, polio, trachoma, intestinal worm infections and infectious diarrhoea, which are known to kill 760,000 children under the age of five worldwide every single year.

The lack of sanitation and access to clean water also has a tremendous economic impact, not least of all by keeping women out of the economic engine and kids out of school. “Doing nothing is costly” says U.N. Deputy Secretary-General Jan Eliasson. “Every $1 spent on sanitation brings a $5.50 return by keeping people healthy and productive.” According to World Bank estimates, poor sanitation costs India an estimated $53.8 bill (6.4% of GDP), Pakistan $4.2 bill (6.3% GDP) and Cambodia $448 million (7.2% of GDP).

“Infrastructure improvements are the most pressing need in addressing these deficits”, Jackson Ewing, director of Asian Sustainability at Asia Society Policy Institute, told AlterNet. “Progress on WASH [water, sanitation, hygiene] requires financial prioritization from governments and capital from development banks and private investment” He added that “the case must be made to finance ministries in places like South Asia and SE Asia that more resources should be allocated to improving water supply, building sanitary toilets, and rolling back water pollution.”

Getting governments to prioritize water issues can be tricky. In many parts of the world, as throughout human history, water is a highly valued and guarded resource. Put another way, you don’t want your enemies to have water. From the Middle East to Africa, from the Indian subcontinent to Asia, many nations have been willing to go to extremes not only to protect their water security, but to use water as a military weapon.

“Geopolitics and a history of cross- border disputes have meant that trans- boundary water issues are perceived largely from a perspective of national security,” writes Mandakini Devasher Surie, the Asia Foundation’s senior program officer in India.” She says that a “highly securitized approach has severely limited access to water and climate data.” By not sharing critical regional water data, Surie argues, it is difficult to get an accurate assessment of water availability. And you can’t solve the problem if you don’t know the extent of it.

To be sure, the water crisis has primarily impacted the developing world, but with ongoing water pollution concerns and climate impacts such as drought, wildfires and marine dead zones increasingly troubling rich nations across Europe and North America, developed countries are coming to realize that they are not immune.

“We don’t know anyone who goes thirsty,” said Water.org’s Damon. “We have faucets everywhere. Our toilet water is cleaner than what 663 million people drink. The recent crisis in Flint, Michigan, ironically, is one of the first times, at least in my memory, that Americans have become aware of just how necessary clean water is, and the dire consequences of not having it.”

In fact, the residents of Flint may have had their human rights violated due to the unavailability of clean water. At least nine current and former Michigan state employees face charges relating to allegations they covered up inform- ation about the lead contamination of Flint’s drinking water. “The fact that Flint residents have not had regular access to safe drinking water and sanitation since April 2014 is a potential violation of their human rights” said Léo Heller, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation.

When it comes to access to clean water and sanitation, we have come a long way. But with a larger water availability crisis looming, a rapidly growing popul- ation, and other concerns occupying the focus of world leaders, it’s clear that ensuring this basic human right could be humanity’s greatest challenge.

Source: Alternet, 18 October 2016 http://www.alternet.org/environment/theres-global-crisis-looming-2030-four-out-10-people-wont-have-access-water?

The references for statements referred to in the text may be found in the original source.

Reynard Loki is AlterNet’s environment editor