Choosing unemployment: what of job seekers? – part 1

John Haly

Unemployment is a choice made by governments, corporations and central banks. It is not within the control of the individual. For numerous decades, the political elite has continuously advocated gradually dismantling the public sector and engaging businesses like PWC, or privatizing public monopolies like Qantas, Telstra, and the power grids (Dickinson, 2023). The corporate capital class campaigned for these outcomes (James, 2016). This clique aims to utilise the potential risk of unemployment as a stick for working class compliance irrespective of working conditions and stagnating wages (Hurley, 2023). Central banks make the decision to purposefully increase unemployment when they feel that the existing level is insufficient and should be increased (Redman, 2023).

According to the RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia), consumer demand has a significant impact on inflation. Furthermore, it is the notion of the RBA’s Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU), which the RBA believes is 4.5% (Hutchens, 2023). It is worth noting that the ABS claims that Australia’s current unemployment rate is 3.7%. The discrepancy that exists between the NAIRU and the actual unemployment rate is said to add to inflationary pressures and is seen as a predicament for the general populace. However, once again, the issue is not managed by the populace but rather by the agency of the ruling classes. The NAIRU’s inadequacies, as well as the fact that inflation was initially affected mostly by supply rather than demand, were addressed in a previous article titled “Monetary and Fiscal Policy Frameworks for Australia Part 1” (Haly, 2023).

The Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU), is a theoretical framework that has been criticized for its measurement and prediction issues (Quiggin, 2023). Its application to measurements exceeding 2 percent should have been questioned, especially in regard to Australia’s post-World War II economic situation. The 1950s and 1960s were times when the labour market in Australia approached full employment. Following the effective implementation of the Full Employment policy in Australia by PMs John Curtin and Ben Chifley, the country experienced a continuous period of 25 years with a low unemployment rate averaging 2%. This occurred in the absence of major inflationary pressures. Robert Menzies faced a serious election challenge in 1960, when the unemployment rate hit 53,000, which accounted for nearly 3% of the labour force. Nonetheless, unemployment eventually rebounded to 2%. According to Anthony O’Donnell’s book, there were measurement flaws in how unemployment was measured, although methodology issues will be discussed shortly (O’Donnell, 2019.

Pg 78-85). In the early 1970s, the Australian government, led by Prime Minister Whitlam, decided to break its commitment to full employment in the aftermath of the Oil Crisis, and unemployment soared to 4.6% in late 1975. (Millmow and Courvisanos 2006. pp. 114,130)

As a consequence, unemployment rates increased significantly and inflation levels increased significantly. The Phillips curve lost some credibility as a result of stagflation in the 1970s, but the NAIRU developed amazing adaptability without justification. “By the late 1980s, it was clear that the NAIRU was no more stable than the Phillips curve had been. Steady increases in the NAIRU led one cynic to observe that the estimated rate always seemed to be 2 percent higher than the actual rate of unemployment (Quiggin, 2010. Pg 114).” However, this zombie economic perspective has re-emerged, despite disinflation since the start of 2023, with the low level of unemployment described by the RBA as being too low (Saphore, 2023). All ostensibly for the purpose of alleviating unease caused by the ABS’s current unemployment claim of 3.7% an excess far beyond that which threatened to cost Menzies the election 62 years ago.

The purpose of this study is to argue that the reported unemployment rate of 3.7% does not accurately reflect the experience of the unemployed. The ABS figure, on the other hand, serves two fundamental functions:

- Comparative analysis on an international scale

- The inerests of capitalist class exploitation.

The fundamental aim of the study is to adequately inform about the magnitude of unemployment and to provide a practical basis for policy, monetary or fiscal.

The ABS approach in assessing employment in accordance with ILO methodology has long been criticised (a) by the Australian Policy Online (APO) platform (Anderson and Richardson, 2023), and (b) in “The Australian,” written nearly a decade ago (Keen, 2014)

As Anthony O’Donnell noted, the labour force survey can be described as “imperfectly realised” (O’Donnell, 2019. Pg 77). It aligns with the guidelines established by the International Labour Organisation’s Conference on Labour Statistics in 1947. These were adopted by Australia in 1964. The utilisation of an international standard to distinguish unemployment rates among countries serves a significant purpose. This does not include for assessing internal or domestic unemployment, the lack of employment or welfare compensation. It is still “imperfectly realised”. The primary domestic purpose of the ABS is to gauge the unhindered accessibility of labour to employers. As Gareth Hutchens has noted it is “focused on solving immediate problems for employers” (Hutchens, 2021). In brief, it assesses the specific group of individuals actively seeking employment, impelled by urgent need and possessing no discernible barriers to employment. It is a subset of Australia’s internal or domestically unemployed people. It is not a complete set. The utilisation of this measure to ascertain the unemployed population in Australia is not appropriate for government policy. I will provide additional elaboration on this in subsequent sections of this discourse.

Despite Treasurer Dr Jim Chalmers’ stated objective of pursuing Full Employment (Chalmers, 2023), the Job Summit held in September 2022 failed to achieve significant advancements (Haly, 2022b). The primary objective of the summit did not revolve around resolving the prevalent and currently exacerbated issue of unemployment.

In contrast, Jim Chalmers wanted to augment the Permanent Migration Programme planning level to 195,000 for the fiscal year 2022-23 (Coorey, 2022). This proposed adjustment is presumed to alleviate the current and large deficiencies in vital skills by reinstating 465,000 additional fee-free TAFE places, with only 180,000 in the following year (Commonwealth Treasury, 2022). Free higher education, an Australian policy adopted initially by PM Gough Whitlam, is still functioning in many less economically advantaged European countries. The opponents of free tertiary education argue on the grounds of financial feasibility.

Although an extended explanation of how that costing is achievable, would draw attention away from the point of employment issues (Mitchell, 2023). Sufficient to say, a country that can allocate a large budget of $368 billion to the acquisition of unsuitable submarines should be able to prioritise expenditures in its people’s education (ICAN Australia, 2022. Pg 11). Setting priorities is a crucial consideration. As stated in the introduction, this all revolves around the concept of political choice.

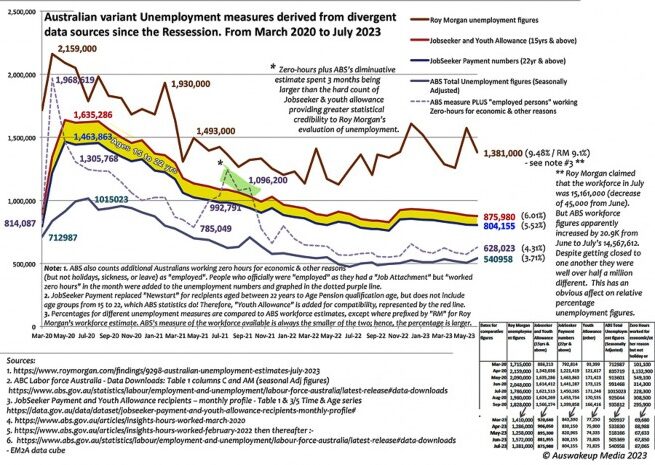

Jim Chalmers has proposed allocating funds to enable the free provision of a specific range of TAFE courses to encompass 180,000 places to be delivered in 2023. That figure pales against the magnitude of the unemployment issue. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) unemployment estimate of 473,000 provided during the summit was lower than the count of individuals receiving “JobSeeker” benefits. This is a consistent trend in all data currently available (see Figure 1). The approach of the current federal government has little genuine commitment. It resorted to superficial measures that merely create an illusion of taking action. And its approach aligns with the interests of its corporate capitalist donors, who will benefit from the availability of inexpensive immigrant labour (Coates & Wiltshire, 2023).

Part 2 of this article will appear in the next issue of ERA Review.

John Haly is a qualified multimedia and graphic designer, as well as video and film producer and freelance journalist He has published extensively, is secretary of the film collaborative, NAFA, and is a founding member of the Australian Arts Party. He also possesses a B.Bus degree, and currently is studying for the degree of Master of Economic Sustainability.

References

Anderson, L., & Richardson, D. (2023). The tip of the iceberg: measuring unemployment in Australia. The Australia Institute. Retrieved from https://apo.org.au/node/324013

Chalmers, D. J. (2023, July 28). Opinion piece: Full employment debate welcome and overdue |Treasury Ministers. Retrieved from ministers.treasury.gov.au website: https://ministers.treasury.gov.au/ministers/jim-chalmers-2022/articles/opinion-piece-fullemployment-debatewelcome-and-overdue

Coates, B., & Wiltshire, T. (2023, May 24). Exploitation of migrant workers is a national shame. Retrieved from Grattan Institute website: https://grattan.edu.au/news/exploitationofmigrant-workers-is-a-national-shame/

Commonwealth Treasury. (2022, September 2). Jobs and Skills Summit September 2022 – Outcomes. Retrieved from https://treasury.gov.au/ website: https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/inline-files/Jobs-and-Skills-Summit-Outcomes-Document.pdf

Coorey, P. (2022, September 2). Permanent migration intake boosted to 195,000. Retrieved from Australian Financial Review website: https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/permanent-migration-intake-boosted-to-195-000-20220902-p5betz

Dickinson, H. (2023, June 7). How reliance on consultancy firms like PwC undermines the capacity of governments. Retrieved from The Conversation website: https://theconversation.com/how-reliance-on-consultancy-firms-like-pwc-undermines-the-capacityof-governments-207020

Haly, J. (2022b, September 1). Stagnating Summit’s Shortfalls. Retrieved from The AIM Network website: https://theaimn.com/stagnating-summits-shortfalls/

Haly, J. (2023, January 19). Monetary and fiscal policy frameworks for Australia part 1. Retrieved from Economic Reform Australia website: https://era.org.au/monetary-andfiscalpolicy-frameworks-for-australia-part-1/

Hurley, B. (2023, September 15). Millionaire CEO wants unemployment to jump by 50% to cause “pain in the economy.” Retrieved from The Independent website: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/tim-gurner-property-developer-australia-b2411998.html

Hutchens, G. (2021, October 16). Why are millions of unemployed people excluded from our monthly “unemployment” data?. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-17/why-are-millions-of-unemployed-people-excluded-from-thedata/100543854

Hutchens, G. (2023, June 25). The Reserve Bank wants more unemployment. It should be applauded for admitting it. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/202306-25/the-rba-wants-more-unemployment-lets-applaud-it/102506500

ICAN Australia. (2022, January). TROUBLED WATERS: nuclear submarines, AUKUS and the NPT. Retrieved from https://icanw.org.au/ website: https://icanw.org.au/wpcontent/uploads/Troubled-Waters-nuclear-submarines-AUKUS-NPT.pdf

James, D. (2016, September 12). The bad business of privatisation. Retrieved from Eureka Street website: https://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article/the-bad-business-of-privatisation

Keen, S. (2014, August 11). The truth about Australia’s unemployment rate “shocker.” Retrieved from The Australian website: https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/thetruthabout-australias-unemployment-rate-shocker/news-story/deb6f41ef2df6cc72730e9a5c2a7617e

Millmow, A., & Courvisanos, J. (2006). How Milton Friedman came to Australia: a case study of class-based political business cycles. [An earlier version of this article was presented at the History of Economic Thought Society of Australia. Conference (18th: 2005: Macquarie University, Sydney).]. Journal of Australian Political Economy, 57(57), 112. Retrieved from https://www.ppesydney.net/content/uploads/2020/05/How-Milton-Friedmancame-to-Australia-a-case-study-of-class-based-political-business-cycles.-.pdf

Mitchell, W. (2023, May 29). Education should be a nation-building investment not a tax on graduates. Retrieved from William Mitchell – Modern Monetary Theory website: https://billmitchell.org/blog/?p=60866

O’Donnell, A. (2019). Inventing unemployment : regulating joblessness in twentieth-century Australia. Oxford ; New York: Hart.

Quiggin, J. (2010). Zombie Economics How Dead Ideas Still Walk among Us. Princeton University Press. Retrieved from https://eldivandenerdas.files.wordpress.com/2011/12/zombie-economics.pdf

Quiggin, J. (2023, September 19). Living in the 70s: why Australia’s dominant model of unemployment and inflation no longer works. Retrieved from The Conversation website: https://theconversation.com/living-in-the-70s-why-australias-dominant-modelofunemployment-and-inflation-no-longer-works-211487

Redman, C. (2023, August 30). Why Does the RBA Want More Unemployed Aussies? Retrieved from The Australia Institute website: https://australiainstitute.org.au/post/whydoesthe-rba-want-more-unemployed-aussies/

Saphore, S. (2023, June 20). Australia’s unemployment rate needs to rise to curb inflation, top central banker says. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/markets/australias-unemployment-rate-needs-rise-curb-inflation-top-cbanker-2023-06-20/

Pingback:Choosing unemployment: what of job seekers? – part 2 – Economic Reform Australia