Augusto Graziani’s legacy – Steve Keen

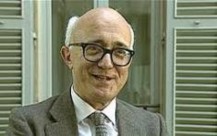

In January this year the Italian economist Prof Augusto Graziani died at the age of 80. Augusto who, you may ask? Graziani’s name is not widely known even among economists, let alone the general public, because he was outside the neoclassical mainstream – and also outside continental America, which has a pseudo-monopoly on fame in economics these days. His Wikipedia entry emphasises his current obscurity: it is a mere stub.

However within the post-Keynesian community, and especially within its European branch, Graziani was a giant. He deserves to be much better known, and I hope that history is far more fulsome in its praise of him than the contemporary world has been, where the chatter of neoclassical economists drowns out the wisdom of true sages like Graziani.

Graziani’s most important contribution was to derive from first principles an accurate statement of the fundamentally monetary nature of a capitalist economy. This began with a simple question: can a monetary economy be one in which a commodity functions as money – something like gold, silver, or in a more modern sense, the pseudo- commodity bitcoin, which is “produced” via energy-intensive computation? His answer was no, because such an economy is merely a barter economy with a minor twist. From this he derived the first principle that a monetary economy is one which uses an essentially value- less token in exchange:

The starting point of the theory of the circuit, is that a true monetary economy is inconsistent with the presence of a commodity money. A commodity money is by definition a kind of money that any producer can produce for himself. But an economy using as money a commodity coming out of a regular process of production, cannot be distinguished from a barter economy. A true monetary economy must therefore be using a token money, which is nowadays a paper currency.

His second principle was that this token can’t be an ordinary IOU, like a trade credit issued in exchange for goods, because this still leaves a financial relationship between the buyer and the seller after the goods have been

transferred. A painter who buys paint from a retailer using a trade credit gets the paint, but he also walks away with a debt towards the shop. But if he buys the paint with money, then after the money changes hands, the paint belongs to the painter and he owes the shop nothing. Money is therefore a token which is accepted as a means of final payment by all sellers:

However, to say that a monetary economy makes use of paper currency is not enough to identify a monetary economy. If, for instance, goods are traded against promises of payment such as bills of exchange, any act of trade gives rise to a debt of the buyer and to a credit of the seller. A similar economy is not a monetary economy, but a credit economy. If in a credit economy at the end of the period some agents still owe money to other ones, a final payment is needed, which means that no money has been used. If, on the other hand, final payments were continually postponed and replaced by new promises, buyers would enjoy an unlimited privilege of seigniorage.

Money is therefore something different from a regular commodity and something more than a mere promise of payment.

Graziani then developed three conditions needed to define a monetary economy. In order for money to exist, three basic conditions must be met:

- money has to be a token currency (otherwise it would give rise to barter and not to monetary exchanges);

- money has to be accepted as a means of final settlement of the transaction (otherwise it would be credit and not money);

- money must not grant privileges of seignorage to any agent making a payment.

From this Graziani derived a simple but profound insight that overturned two centuries of economics perceiving capitalism as fundamentally a modified version of barter. In this conventional barter vision, all exchanges involve two parties and two goods: the ideal situation is where Agent A has good X (for example, deer) and wants good Y (for example, beaver), while Agent B has beaver and wants deer. They meet, work out an exchange ratio, swap the respective bundles of commodities, and toddle off to consume their purchases.

Money was treated as a simple kludge between this ideal barter and the more common situation where A had deer and wanted beaver, while B had good Q (say, wheat) and wanted deer. B would first sell wheat in return for some of the designated “money commodity” Z (say, gold). A would then willingly give B the deer in return for gold, because he knew he could then give someone else gold in return for what he really wanted, which was some beaver.

Graziani’s insight was that rather than the 2-person, 2-commodity vision of barter, a monetary economy was one in which every exchange involved 3 people (or institutions), one commodity, and money. A monetary economy is one in which buyer A directs bank Z to transfer money from A’s account to B’s. In return, B gives A the beaver he craves (hmmm… don’t blame me, it’s Adam Smith’s example). In Graziani’s words: The only way to satisfy those three conditions is to have payments made by means of promises of a third agent, the typical third agent being nowadays a bank. When an agent makes a payment by means of a cheque, he satisfies his partner by the promise of the bank to pay the amount due. Once the payment is made, no debt and credit relationships are left between the two agents. But one of them is now a creditor of the bank, while the second is a debtor of the same bank. This insures that, in spite of making final payments by means of paper money, agents are not granted any kind of privilege. For this to be true, any monetary payment must therefore be a triangular transaction, involving at least three agents, the payer, the payee, and the bank. Real money is therefore credit money.

Some people remember where they were when John F Kennedy was shot, or when Princess Diana was killed (or when Miley Cyrus twerked on MTV). I remember where I was when I read documents that profoundly altered how I thought about the world. Reading this paper from Graziani – a single page in a single paper, no less – was one of those occasions.

I was working as a senior lecturer at my ex-employer UWS, and I’d been asked to take over teaching the financial economics course, because the staunchly neoclassical economist who had been lecturing in it was such a bad teacher that there had been a student revolt. There was no way that I was going to serve up the guff that neoclassical textbooks delivered on this topic, so I delved into the strictly monetary literature in economics to construct my own course.

I knew that Augusto Graziani was one of the authors I had to read, because by chance I had heard him speak at a 1998 conference at the University of Bergamo in northern Italy. Not only was his paper insightful, his spontaneous answers to questions from the floor were delivered in perfectly formed English paragraphs. “Augusto” is a grand name for anyone to have to bear – let alone a man who stood barely five feet high – but with his elegant posture and flawless erudition, Augusto carried his name with aplomb.

When I read Graziani’s paper in 2002, a puzzle that had stymied me for years was suddenly solved. How do I move from the implicitly monetary model of financial instability I had developed in 1992, to a strictly monetary one – in which deflation could exacerbate a debt crisis, as it clearly had during the Great Depression? The answer was simple: banks had to become an essential part of my modeling, and every transaction had to follow that triangular structure that Graziani outlined. Triangles and banks, and not two lines between buyer and seller and barter, ruled in monetary economics.

That insight led over time to the development of my Minsky modeling program, which is now an indispensable part of my approach to economics. In building it I truly stood on the shoulders of the giant who was Augusto Graziani. Hopefully a future economics will accord him the status he rightly deserves.

I’ll conclude with a quote from Riccardo Bellofiore’s paean to Graziani in the Review of Keynesian Economics: He reminds us that economic theory has to put at the heart of its discourse not the ‘imperfections’ of the market, but rather the ‘normality’ of power and conflict, not only between labour and capital, but also between fractions of

capital, and between capitalisms. It must abandon the reference to an imaginary world of a barter economy ‘disturbed’ by money, or the delusion that money may be integrated into an economic model, which is non- monetary in its roots.

Source: Steve Keen’s DebtWatch http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2014/01/14/augusto-grazianis-legacy-retains-its-currency/