Equality and fairness: vaccines against this pandemic of mistrust

Tony Ward

The COVID crisis has laid bare a crisis of trust.

In many Western nations there’s a small but significant minority refusing to follow distancing guidelines, wear masks or get a vaccination. Protests in recent weeks have demonstrated just how much they mistrust politicians, scientists, bureaucrats, the “mainstream media” and many of their fellow citizens.

And that’s a problem — because higher trust levels have been shown to be associated with markedly better outcomes in handling the virus. As the World Happiness Report 2021 published in March concluded, generally the higher the level of social trust, the lower the nation’s COVID-19 death rate.

So what can be done to combat this pandemic of mistrust?

Using data on national trust levels published over the past few years, my analysis suggests more than 80% of differences in trust levels between nations can be explained by just two factors: economic inequality and, to a lesser extent, perceptions of corruption.

This calculation underlines the importance of tackling the conditions in which misinformation thrives. Censorship and other blunt instruments have their place, but only treat the symptoms. To treat the cause requires promoting equality and fairness.

What ‘lost wallets’ reveal about trust

The World Happiness Report’s conclusions about the correlation between effective COVID responses and level of social trust drew on past research, including evidence from the 2019 World Risk Poll (sponsored by Lloyd’s Register Foundation).

That poll surveyed more than 150,000 people in 142 nations. One crucial question asked them to imagine losing a small bag of financial value and then say how likely it was that a stranger would return that bag. This question is a staple of social trust research, known as the “lost wallet test”.

For my analysis of the relationship between trust, inequality and corruption, I’ve mainly used another “lost wallet” study published in 2019, by University of Michigan behavioural economist Alain Cohn and colleagues in Switzerland. Their study went one better than asking people about their expectations; it actually tested levels of trustworthiness by “losing” 17,000 wallets in 355 cities across 40 nations and measuring how many came back to their “owners”.

This study broadly found actual returns to be slightly higher than expectations in the World Risk Poll. But both found consistent differences in social trust (and trustworthiness) between nations, in line with other survey results.

The results from the Cohn study are therefore a good measure of both trust and trustworthiness in different countries.

Measuring the impact of inequality

According to my calculations, inequality explains two-thirds (68%) of the differences between countries in social trust levels.

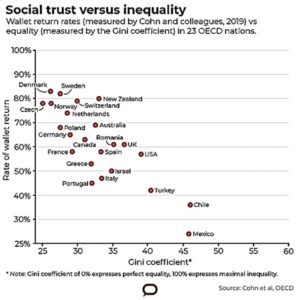

This is shown in the graph below. It uses only the 23 countries in the Cohn study that are members of OECD, because these have the most robust data measuring inequality.

The left Y axis shows the percentages of wallets returned. The bottom X axis shows the Gini coefficient: the standard measure of economic inequality, with the nations closer to 0 being more equal.

There’s a strong correlation between equality and levels of social trust, though clearly other factors are involved as well.

For example, consider the return rate for New Zealand (one of the highest in world), and then Australia, to the lower rates in Spain and Italy (less than 50%), despite all four countries having similar levels of economic inequality.

I calculate close to half of this difference can be attributed to perceptions of corruption. I did this using data from anti-corruption organisation Transparency International, which publishes annual survey of perceptions of corruption across the world and scores countries on a 100-point scale (the closer to 100 being better).

In 2020, New Zealand equal topped the list with a score of 88, compared with Australia on 77, Spain on 62, and Italy 53. (Australia has seen the biggest recent drop of any of these OECD countries, slipping from a score of 85 in 2012).

All up, equality and corruption perceptions appear to explain 82% of the differences in trust and trustworthiness between nations.

Promoting equality and fairness

Correlation doesn’t necessarily mean one factor causes the other. But in this case, there is strong supporting evidence to suggest inequality and perceptions of unfairness fuel mistrust.

As this year’s World Happiness Report noted, higher social and institutional trust levels are associated both with greater community resilience to natural disasters and individual resilience to ill health, unemployment and discrimination. More trusting societies and individuals are also happier.

If this wasn’t strong enough incentive for policies that promote fairness and equality, the epidemic of misinformation and mistrust exposed by COVID-19 should be. As psychologist John Ehrenreich has written in Slate:

Conspiracy theories arise in the context of fear, anxiety, mistrust, uncertainty and feelings of powerlessness.

At the American Economics Association’s annual conference in January, a number of speakers focused their attention on the importance of trust. The Economist magazine summarised their conclusions:

higher levels of trust and social responsibility were associated with less scepticism of media reporting on COVID-19 and greater willingness to accept stringent lockdown measures.

Mistrust has been a major barrier in combating the coronavirus — and will present more challenges in the aftermath. Policies to enhance equality and fairness, and to reduce corruption, are potent vaccines in these tasks.

Source: The Conversation, 3 Aug 2021

https://theconversation.com/equality-and -fairness-vaccines-against-this-pandemic-of-mistrust-160100

Dr Anthony Ward is Fellow in Historical Studies, The University of Melbourne

Dr Anthony Ward is Fellow in Historical Studies, The University of Melbourne