Please, no more questions about how we will pay off the COVID debt

Steven Hail

There are many uncertainties about the next Australian federal election, but one thing is almost completely certain. It is the response that the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition will both give when asked this question:

How are we going to pay off our COVID-19 debt?

Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese disagree on a great many things, but in their answer to this question they will be in perfect harmony.

It will be: “we will need to pay it back in the future by spending less or taxing more — otherwise, we might lack the means to deal with a future crisis”.

They might even talk about “fiscal fire- power” — the need to create a budget surplus in order to have something to spend whenever there’s an emergency.

The strange thing is that although this is for them the safest answer to give, and although it is the conventional wisdom, it simply isn’t true.

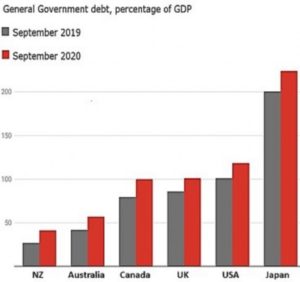

Consider Figure 1. It shows the general government debt as a share of gross domestic product in six countries with similar monetary systems to Australia’s, just prior to the pandemic, and then a year later.

You cannot help but notice that four of the other five countries had more general government debt than did Australia before the COVID crisis, and Japan’s national government had four times as much government debt as Australia.

It made no difference to their ability to spend as needed to support their economies during the pandemic, none whatsoever.

Government debt hasn’t hamstrung responses to the crisis

This means it’s wrong to suggest that our government wouldn’t be able to support its economy, even if it didn’t pay back its COVID-related debt.

You might imagine (it’s been said) that more government debt would drive up interest rates, but of late that hasn’t been the case either.

Indeed, the rate of interest on 10-year Japanese government bonds has been close to zero for five years, because it’s been held there by the Bank of Japan.

Or perhaps you think that more government debt will lead to higher inflation. In Japan and other countries that hasn’t happened either. Japan has had the lowest average inflation rate of these six countries.

And so far it hasn’t stoked inflation

So many myths.

The pivot the federal coalition is taking to winding back spending with the end of JobKeeper and the withdrawal of a liveable JobSeeker payment isn’t needed, and is also unwise.

The reluctance of the federal opposition to support a non-poverty unemployment benefit, as well as its promise to avoid net spending commitments in its election platform, are also unjustified.

Especially in an economy where labour force underutilisation (unemployment plus underemployment) remains over 14%. Nearly two million people are either unemployed or underemployed.

Many more are in insecure employment, including hundreds of thousands whose jobs are now at risk because of the failure to replace JobKeeper with something such as with a federal job guarantee.

It isn’t as though the Australian Greens are speaking from a fiscal script which is that different. The Greens obsess over costing their policies and finding extra tax from resource companies and billionaires to “pay for” their laudable commitments to full employment, social security, education, healthcare, and investment in renewables.

They don’t talk so much about repaying the debt, but they do not want to be accused of adding to it.

The Greens worry like the others

Like the bigger parties, the Greens are reluctant to challenge the narrative of the federal government as a household, with a budget it must manage in order to avoid insolvency.

But the household metaphor is another myth, and it needs to be challenged.

The federal government’s finances have nothing in common with those of a household, however wealthy that household might be, and nothing in common with any business, big or small, or even state and territory governments.

None of these are currency issuers. They all have to generate income or borrow before they can spend, and their borrowing necessarily puts them at risk of insolvency.

Our federal government is different, like the national governments of Japan and the United States. It is the monopoly issuer of the Australian-dollar-denominated currency.

The federal government does not need to increase taxes in order to increase spending, and it doesn’t even need to borrow. Its central bank (RBA) issues currency for it all of the time, every day.

Federal government spending is funded when it is authorised, usually by parliament.

Having spent the national currency into existence, the federal government then usually offers savers the opportunity to convert that currency into Treasury bonds, which usually offer a better rate of interest than transaction accounts with a bank.

Our federal government chooses to sell Treasury bonds – but it doesn’t need to.

This means it can’t be held hostage by the bond market. It can’t be forced into insolvency or austerity. The selling of bonds doesn’t constitute borrowing in the normal sense of the term. It is better described as the exchange of one form of financial asset for another.

At the end of the life of the bond (when the “loan” comes due) it can pay it off (swapping currency for the bond). Or it can issue a replacement bond if it does not wish the balance of financial assets within the economy to change.

And it’s not just my opinion. It is also the view of a senior economist with the US Federal Reserve, David Andolfatto, as expressed in a paper published by the St Louis Fed in December 2020..

Together these considerations suggest we might want to look at the national debt from a different perspective. In particular, it seems more accurate to view the national debt less as a form of debt and more as a form of money in circulation.

President Biden is listening to voices like Andolfatto’s. Australia’s politicians are not. Ours continue to see federal deficits as a burden on future generations, when they are not that at all – they supply financial resources to the present generation.

The national debt is nothing more than the dollars the government has put into the economy and not yet taxed back out. Deficits matter, but not in the way that Albanese and Morrison seem to imagine. They matter because if they become too big, they might stoke too much inflation.

What if our leaders spoke the truth

In an economy with spare capacity (unemployment and underemployment) and with wage setting institutions that make it difficult to argue that there will be significant persistent inflation in the foreseeable future, there is no reason at the moment to wind back spending, not until unemployment and underemployment are much lower.

For the Greens, there is no need for them to tie themselves in knots, arguing on the one hand that they need to shrink coal mining to address climate change and on the other that they need to raise taxes from the mining industry to pay for government services.

Taxes collected from the mining and other industries (and from individuals) don’t fund federal government spending. It is self-funded. And the limits on spending are not imposed by federal tax receipts or the ability of the government to borrow. They are imposed by the availability of productive capacity in our economy and our ability to use that capacity without stoking inflation.

When our leaders are next asked, “how are we going to pay off our COVID-19 debt”, they ought to take a deep breath, look the interviewer in the eyes, and say “we don’t need to, because it is not debt in the conventional sense of the term”.

They ought to tell the public the truth. It’s a novel idea, perhaps, but it would lead to a better educated public and a fairer and better-managed economy.

Source: The Conversation, 6 April 2021 https://theconversation.com/please-no-more-questions-about-how-we-are-going-to-pay-off-the-covid-debt-158056

Dr Steven Hail is a Lecturer in economics at Adelaide University and an ERA member