Letter from Greg Reid

Doughnut economics – a way forward

The book “Doughnut Economics” by Kate Raworth is full of examples and conceptual tools that could redirect economics into the service of a sustain- able society. At heart it hopes that the current economic paradigm will be swept aside because of mounting failures and be replaced by regenerative and distributive economic systems.

Unfortunately, the current economic paradigm is not a failure to those who have been advanced by it and wield power through it. They will use rationalisations and false narratives to cling to the neoliberal system that has served them well. History is full of examples where exploitative systems have persisted for many centuries despite the broad destruction and suffering they caused.

I fear that “Doughnut Economics” will remain an interesting fringe theory unless it can subvert the current paradigm from within, and that will require some initial conceptual compromises during the transition. Like the climate change issue in Australia, taking an idealistic stance can lead to polarisation, delay and then well-funded obstruction.

I suggest that GDP is the back door to assaulting the neoliberal citadel even though Kate Raworth exhorts that we must become “growth agnostic”. GDP growth is a metric that hides many sins, so politicians and orthodox economists will not readily abandon it. However, in clinging to GDP they will compromise and perhaps allow it to be modified into a seductively useful tool of “Doughnut Economics” design.

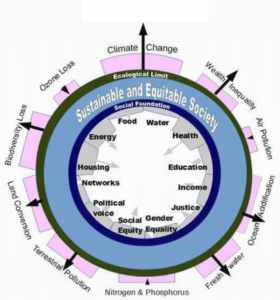

The key “Doughnut” diagram identifies transgressions of ecological limits extending beyond an outer circle, and shortfalls in basic needs falling inwards from an inner circle. In a national picture, I suggest that each external sector of environmental damage should be sized on a scale of cumulative GDP loss, and accompanied by an arrow representing the rate of growth of this cost.

A glance at the outer circle will reveal the biggest problems with the fastest growth. The problems can be address- ed by measures that are generally cost neutral or revenue positive such as regulation, taxation and trading schemes.

The inner circle of social shortfalls could be quantified through the investment required to redress the problem plus an arrow representing the rate of growth in the shortfall. In this way priorities could be identified for public and private investment.

Though imperfect, this doughnut quantified in terms of GDP greatly simplifies budgetary choices in a schematic easily presentable to the public. Bureaucrats would be drawn to this compass, and neoliberal economists could see it as an escape route from failing theory. In this time of burgeoning fringe parties, the centrist politicians would find powerful cachet in an approach which gives voters a sense that the important problems are being addressed and improvements will come.

I strongly argue that an external sector should be added for “Wealth Inequality”. Humans are a key part of the ecosystem and over-exploitation of that ecosystem is largely driven by unequal wealth. The main tools to address the problem are progressive taxation and regulation. The doughnut’s “Social Equity” sector in the inner ring is an entwined problem, but belongs in the inner circle of investments to improve opportunity and access. While the Gini index yields a ratio of wealth inequality, to maintain comparison with the other sectors of the doughnut the cost must be measured in dollar terms of such things as unemployment, underemployment, property crime, policing, housing inflation, recurrent social security costs etc.

For those still wedded to a single GDP figure, they could use Net GDP after the costs of the inner and outer circles are subtracted. Net GDP can grow even if gross GDP does not, and society would learn to become “growth agnostic”. In countries where GNI is the dominant economic metric it could be applied instead of GDP. The point is that if “Doughnut Economics” is to succeed it must subvert and seduce the dominant paradigm since waiting for a neoliberal surrender will likely invite dismissal or overwhelming counterattack.

A Doughnut Tool

Comments from Elinor Hurst

Comments from Elinor Hurst

This article would have profited from a brief explanation of what the “doughnut” is at the start, before plunging into a critique.

In regard to assessing so-called GDP loss, there are massive problems in attempting to do this. For example, how does one cost the loss of biodiversity? Or microplastics and other residual pollutants? This is why the GPI was developed, which is a more mature concept. However even GPI does not take into account planetary limits, which is the key significance of the outer boundary of the doughnut.

Also it is unclear why the author is insisting on revenue neutrality. This feature is not essential, and needs to be justified if it is going to be included.

The author argues that an external sector should be added for “wealth inequality”. However this is a social indicator which only indirectly leads to ecological damage. And so placing it in the outer ring could be confusing.

The author also says that net GDP could be used after the costs of the inner and outer circles are subtracted. This is exactly what the GPI is designed to do, which should be acknowledged.

Comments from Assoc Prof Philip Lawn

Although I like much of what Kate Raworth says in her book, I don’t think the doughnut diagram adds a lot to what has already been shown by other indicators.

The diagram is designed to show the symptoms, not the causes. I agree with the other reviewer that wealth inequality should not be on the outside even though I agree with the author that inequality drives a lot of environmental damage. It should be on the inside. In fact, you could argue that failure to deal adequately with all aspects inside the doughnut can be a cause of environmental damage. Why single out wealth inequality?

I agree with Elinor Hurst about the revenue factor, which I presume means the revenue generated by the government. This is irrelevant if the central government issues the national currency and therefore has no fiscal constraint. The author’s statements reveal a lack of understanding of modern monetary theory.

I agree with the author about the role of power interests in maintaining the status quo. I disagree with the view that one should not be idealistic. Idealistic perspectives highlight what is wrong; where we ought to aim; and how we can get there. It is crucial to changing people’s views and initiating change from within, which is what the author says is necessary to bring about positive change.

Of course, one cannot expect to jump to an ideal situation overnight. It is therefore just as important to explain how best to make the transition. This is where a job guarantee and other equity measures are important — they can prevent the most vulnerable from having to pay a cost for the change that is required.

The author has income inside the doughnut. What does he mean by income? GDP?

GPI? If it’s GDP, then more of what is supposed to make us better off is a driving force behind many environmental damages. It should be the GPI. Perhaps ‘income’ should be replaced with ‘economic welfare’. The GPI measures economic welfare, which recognizes the costs as well as the benefits of economic activity.

I don’t like the idea of costs being measured in terms of GDP losses. The Stern Review on climate change did something similar. I believe the impact of ecological overshoot should be measured in terms of its effect on the GPI, which I talk about in my climate change book. Having said this, ecological sustainability is about avoiding the transgression of planetary boundaries, and has nothing to do with costs. Measuring the cost of environmental damage is required to calculate the GPI. Only the biophysical indicators can inform us about whether we are operating sustainably or not.

It is very difficult to precisely measure the costs of environmental damage, but these costs are also estimated when calculating the GPI. Better to include an imprecise estimate of the environmental costs than to ignore them altogether