An interconnected economic reality Part 2

Dynamic change and complexity in economics and modelling Dennis Venter

This article is a continuation of part 1, by the same author, which appeared in the previous issue.

3. A template for robust policy advice

Some economists use algorithms to create computer simulations of societies and then test policies inside these simulations. However, these results often foster a false sense of certainty if taken out of context. It is important to ask whether such models are based on an accurate picture of reality. Towards this end, I believe we can learn a lot by looking at naturally occurring simulations that exist in the real world!

It is essential to recognise two points: Firstly, the particular economic issue being addressed is a dynamic one with roots in each quadrant. Secondly, the policy itself will cascade across this interconnected space. We can see this process in action during the emergence of a new sport, where the rules evolve in tandem with the capabilities of players enhanced by equipment, the features of the physical playing field, as well as the players’ goals and strategies.

The genesis of a new sport usually lies with a group of individuals who have certain things in common. These individuals recombine objects and features of physical spaces in new ways and adapt the rules of existing sports for use in the new sport. This is a realworld simulation of how new technologies and institutions are created. It captures the basic process of innovation and it is completely imbedded in the four quadrants.

In sports, new gear and changes to the court or rink are introduced in an obvious manner, and when players outsmart the system it is typically detected, facilitating rule-making. However, in economies, the policymakers need to consider a constantly changing situation where new things spread fairly quickly across cities and regions. Take e-scooters or food delivery on bicycles for example, policymakers need to think about all four quadrants to make effective policy.

Before the neoclassical perspective came to dominance, the focus was indeed on understanding this bigger picture, how its parts interact, and even how the entire system evolves with time and with increases in community size. For more on how to restore the fortunes of this earlier economic thought, I recommend reading From Economics to Political Economy, by Tim Thornton (2017).

4. What we thought we knew, and the changes ahead

One step at a time, humanity is gaining awareness of the ‘complex’ systems that make up our reality. The first steps on this journey were taken by philosophers long before the familiar use of the word. Republic by Plato can be seen as an attempt to identify subsystems of what he believed to be proper societies and provide advice on how to manage these systems for supreme macro results. These early steps merely involved realising that the big system exists out of small systems and that there is a link connecting the two.

This link, in ancient times, was seen as divine and unchanging. The closer a city got to this ‘golden path’, the more civilised they were deemed to be. However, our understanding continued to evolve, revealing a deeper comprehension of how parts of a system connect and develop over time.

Often, what we perceive as a ‘general mechanism’ is merely a transient result of deeper processes. As a system develops, past decisions lock a society onto a path that leads to the formation of new structures, the opening of new possibilities, and the closing of others.

In Politics, Aristotle discussed the evolution of societies from small familial units to large political entities like citystates. He described how families naturally form villages, which in turn form city-states, illustrating how progress unfolds over time and how the system differs from one point in time to the next. While his views on social organization remain influential in political philosophy and sociology, it is important to note that not everything is deterministic. Choice and path dependency mean evolution has a mix of taxonomic and random characteristics.

Thorstein Veblen (1898), one of the founders of evolutionary economics, gave an even deeper description of the dynamics operating in economies, however, eventually every past thinker will be surpassed by those who can look into larger and more complex societies of their own time.

Neoclassical models have no use in analysing evolving economies. As Joan Robinson (1980) warned, our relations to an event in the past and

an event taking place today are radically different. She criticised the construction of models that trace the effects of a particular event over time while keeping all else constant as idle amusement in creating something with no direct applications to reality. She said we should forget about grand laws and see how things actually happen. Robinson’s warning means that models need to evolve as quickly as the world does. How might a quadrant framework evolve in the future?

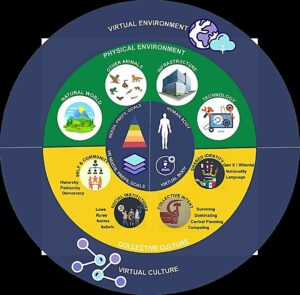

One potential change could stem from advances in Virtual Reality (VR) technology. Platforms like the ‘Metaverse’ and applications such as ‘VR Chat’ facilitate social interactions where users engage as digital personas that are called avatars. Avatars are fully customisable, and people put a lot of time, effort, and even money, into designing their avatars. From this virtual human-environment interaction, VR culture is emerging and VR laws are being debated. For example, abuse, racism and assault cannot be regulated without total surveillance of the VR environment. As this technology evolves and virtual spaces become more immersive, it may develop a variety of uses and extend into various parts of our economies and daily lives (see Figure 4).

Path dependence implies that one change is never just one change. Technology is intertwined with our physical and cultural world to such an extent that when one looks back, it almost seems as if it has a life of its own, locking us onto a certain path. To predict and direct this path, robust policies require a robust understanding. So what connections do you see in Figure 4?

References

1 Gigerenzer, G. 2012, Ecological rationality: Intelligence in the world, Oxford University Press, New York.

2 Graham, M. The Relationist Ethos, Greenprints. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8afvrlkpxy4 [Accessed 14 Apr 24]

3 Ostrom, E. 1992, Governing The Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge Univ Press, UK.

4 Raworth, K. 2017, Doughnut Economics,

Chelsea Green Publishing, London.

5 Robinson, J. 1980, ‘Time in Economic Theory’, International Review for Social Sciences, vol. 33, issue. 2, pp. 219-229, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.1980.tb02632.x

6 Simon, H. 1947, Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organisation, Macmillan,NY 7 Thornton, T. 2017, From Economics to Political Economy, Routledge, New York. 8 Tieleman, J. and De Muijnck, S. 2021, Economy Studies, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

9 Veblen, T. 1898, ‘Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science?’, Quarterly Journal of Economics. vol. 12, issue 4, pp 373-397, doi: 10.2307/1882952

Dennis Venter is a member of Rethinking Economics Australia and also part of the Behaviour & Society working group at the Young Scholars Initiative. He is a postgraduate student at the University of Sydney, where his thesis is on the foundations of complexity in economics and modelling.