An interconnected economic reality Part 1:

Rethinking the economics curriculum Dennis Venter

This is the first part of an article by Dennis Venter describing an integral approach to the dynamics of a modern economy.

There is an obvious but often overlooked secret in Economics 101 textbooks. In the first chapter, you find a few divergent definitions of economics but no explanation for their variance. The secret is that these definitions stem from distinct perspectives of economics, yet the textbook adopts only one perspective. Such textbooks take a monist approach and create a monoculture of economists, stunting their ability to see the world from different perspectives.

I have been part of initiatives like Rethinking Economics and Exploring Economics where we try to teach different perspectives to students and push for curriculum change. The Rethinking Economics textbook and the Exploring-Economics.org website are examples of our efforts. However, both of these take a pigeonhole approach, containing 9 or 10 perspectives on how the economy works. The book has a chapter for each and the website places each perspective in a box and then compares these boxes and since reality does not fit neatly into boxes, deciding which perspectives to include is a topic of debate and ultimately exclusion.

Fresh thinking is required to come up with an alternative. A possible solution might be an integral approach that brings all perspectives together in a dynamic picture of economic reality.

1. Economic Reality

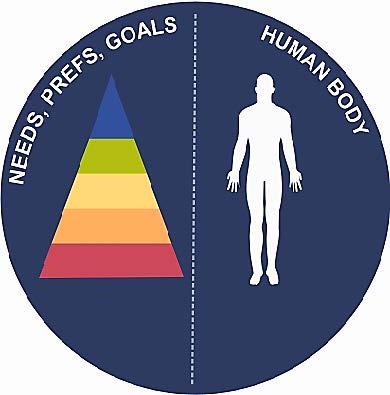

The first step is to put aside the pretend-pretend “representative agent” used in Economics 101 and instead consider an actual individual. Envision a unique human being with genuine needs, preferences and goals just like yourself. Each individual would also possess certain physical abilities. Both the internal (needs, preferences, goals) and external (physical abilities) aspects of the individual are relevant in economics as they shape every decision and action taken by the individual (see Figure 1).

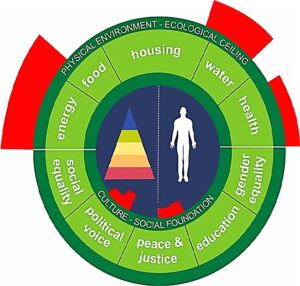

The next step is to realise that an economic system is not merely a simple sum of all these individuals. If it was, our world would look vastly different. Rather, an economic system comprises complex connections and feedback loops among individuals and other tangible and intangible elements. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of this.

At the top of the diagram lies the physical environment, which encompasses among other things, the natural world and other organisms. In fulfilling our needs and goals (middle of diagram), we utilise this physical environment to build infrastructure and technologies. Due to the presence of feedback loops, not only do we change the environment but the environment also changes us (physically and psychologically) – and it is a cycle that has existed for millennia.

Emerging from this human-environment interaction is the cultural environment, located at the bottom of Fig 2.

Here, we deal with things such as:

Social structure, or how the individual fits into the community. For example, is it mostly a strict hierarchy like in the West, a small lateral society with individual autonomy, patriarchy, or monarchy?

Social Institutions. For example, a society’s legal and belief systems that contain all manner of lore, rules and laws, both written and unwritten. Other examples include the financial system, governance system, education system, or even systems you follow without knowing it, such as forming a queue at a checkout.

Collective goals. For example, collective goals arise from central governments, cartels, political parties, or any collective of people. An empire tries to dominate, a market society tries to compete, an intentional community may have a goal of managing common pool resources, etc.

Shared identity. For example, we are Aussies, we are millennials, or we speak English.

The ethos of a nation, including the First Nations people of Australia (see Mary Graham’s Relationist Ethos of 2023) can be associated with the quadrants depicted in of Figure 2. So can twenty-first-century capitalist society; capitalism tends to evoke our competitive instincts, and this competition, in turn, sustains the system.

Through connections and feedback, a specific system reinforces specific behaviour.

As explained above, not only does the system (outer circle) interlink with the individual (inner circle), but even the physical and cultural environments (top and bottom) reflect each other.

Connections crisscross the diagram allowing change to bounce all around the framework.

For example, the effects of a physical change at the top, like big agriculture, cause a shift in social structure from flat systems to hierarchies (at the bottom). It also leads to changes in the individual’s needs, habits and goals (in the middle). Surpluses lead to the appearance of empires and further shifts in culture (bottom). Eventually, as we enter the industrial age, nature becomes commodified (top), laws are made to go along with it (bottom), and the need for growth, to compete, and to be profitable gets its modern meaning.

Also note the individual’s need for access to networks, information, goods and services, all of which are required continually to function in a modern system. Yanis Varoufakis (2024) argues that we have entered a new system called technofeudalism where we depend on platforms to access most of these things. The framework is a tool that can be used to trace the dynamics of a complex reality under constant evolution.

2. One framework, but with many perspectives

How do different economic perspectives relate to this framework?

Neoclassical economics focuses solely on the need for ‘goods and services’ produced by firms. This is one isolated sliver of the full picture and relying solely on this perspective overlooks many crucial dynamics.

The neoclassical approach assumes complexity away for the sake of using mathematical equations. Production, consumption, and the value of goods and services are understood in terms of the neoclassical supply and demand model. This model assumes that consumers have so-called “rational” preferences for different bundles of goods and services which can be identified and associated with numerical levels of pleasure. Consumers maximise pleasure, firms maximise profit, and both parties act independently with perfect knowledge. Economic equilibrium is then obtained by solving these demand and supply equations simultaneously.

However, by looking at Figure 2, it becomes obvious that markets do not function autonomously. Trying to represent them as isolated entities in models will yield inaccurate results. Furthermore, market processes are only one aspect of the broader picture. Central planning is used by governments to deliver certain services and communities may manage common pool resources by distributing responsibilities and making their own rules (bottom) depending on which resources (top) they oversee (Elinor Ostrom discussed this extensively in 1992).

All of these mechanisms form part of modern economies and are discernible in Figure 2.

Feminist economics highlights patriarchy’s dominance. The framework can be used to visualise links that result from this and it reminds us to consider all needs (inner left), like the need for care not provided through markets.

Ecological economics has a strong focus on human’s place in ecology. This is observable in the diagram, too.

Austrian economists realise that markets are complex systems. This is a great leap forward from the oversimplified way neoclassical economists think of the market. The diagram helps us to see that such complex markets are also embedded in a complex social and biological environment. The diagram helps us to think about interactions between complex markets and other complex systems.

Behavioural economics is also depicted more accurately. The diagram shows that truly rational behaviour depends on habits and beliefs and the whole system as it has evolved up to the point in time. Herbert Simon, the father of behavioural economics, argued the same in 1947, and Gerd Gigerenzer echoed this view in 2012.

Complexity economics uses algorithms to model agents and relationships, however it still needs a clear picture to base algorithms on.

How money or debt has developed over centuries can be outlined by referring to the quadrants. Here, one can consider social aspects that are relevant to this development, such as trust in small communities, how things changed in hierarchical communities, how physical things in the environment (coins, cards, etc.) took on the function of debt, and how technology plays a role in this process.

Mapping a local economy within this framework allows opportunities for economy studies as advocated for in the book of the same name by Tieleman & De Muijnck (2021).

The doughnut from Kate Raworth (2017) also integrates well with the framework (see Figure 3). At the top of the doughnut, the physical environment matches with things like energy, food, and housing, while the cultural environment at the bottom is linked to peace, equality and education. The framework reveals the structures that operate behind the situation in the doughnut!

Therefore, instead of adopting a single perspective or juxtaposing multiple perspectives, an integral approach that sees economics as emerging from a changing individual inside a changing social and physical world offers many advantages.

References:

1 Gigerenzer G. 2012, Ecological rationality: Intelligence in the world, Oxford University Press, New York.

2 Graham M. The Relationist Ethos, Green-prints. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8afvrlkpxy4 [Accessed 14 Apr 24] 3 Ostrom E. 1992, Governing The Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action, Cambridge Univ Press, UK.

4 Raworth, K. 2017, Doughnut Economics, Chelsea Green Publishing, London.

5 Robinson, J. 1980, ‘Time in Economic Theory’, International Review for Social Sciences, vol. 33, issue. 2, pp. 219-229, doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.1980.tb02632.x

6 Simon, H. 1947, Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organisation, Macmillan,NY

7 Thornton, T. 2017, From Economics to Political Economy, Routledge, New York. 8 Tieleman J. and De Muijnck S. 2021, Economy Studies, Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam.

9 Veblen T. 1898, ‘Why is Economics not an Evolutionary Science?’, Quarterly Journal of Economics. vol. 12, issue 4, pp 373-397, doi: 10.2307/1882952

Dennis Venter is a member of Rethinking Economics Australia and also part of the Behaviour & Society working group at the Young Scholars Initiative. He is a postgraduate student at the University of Sydney, where his thesis is on the foundations of complexity in economics and modelling.

Part 2 of this article (appearing in the next issue) will explain how this framework can provide a template for robust policy advice.