Why mainstream economists’ theory of finance is useless

Ismael Hossein-Zadeh

Following in the footsteps of the financial big wigs at the head of the Federal Reserve (Alan Greenspan, followed by Ben Bernanke), most mainstream neo-classical economists optimistically projected that the financial expansion of 2002-07 would continue indefinitely. Not surprisingly, the 2008 market collapse was a huge surprise to them, or as Chris Giles of the Financial Times put it, “left them with ample egg on their studious faces” (November 26, 2008).

A major reason for these economists’ bewilderment in the face of financial bubbles and bursts is that, according to their theoretical shibboleth, expansion of finance/fictitious capital on a macro or national level is not supposed to deviate much from that of industrial/real capital, as the magnitude of the former is essentially determined or limited by the requirements of the real sector of the economy. The theory maintains that there is an auspicious synergy between the financial and real sectors of an economy: finance capital tends to shadow industrial capital as if its main function is to grease the wheels of the real sector, that is, of manufacturing and commercial undertakings – just as was more or less the case in the early stages of capitalism, when there was not yet a large, independent financial sector [1].

This theoretical mindset of neoclassical economists, of both the neoliberal and Keynesian traditions, follows from their faith in the (barter-like) Walrasian general equilibrium model in which there exists a continuous balance between supply and demand, or between income (as the monetary equivalent of supply) and expenditures (as the monetary equivalent of demand). Production is the starting point in this model: as manufacturers employ labor and means of production to produce goods and services, they also generate income in the form of cost of production, that is, in the form of wages/salaries, interest income, rental income, etc. As the recipients of the incomes generated turn around and purchase what they have produced, they thereby also establish equilibrium between income and expenditures, or between supply and demand. The income – expenditure balance here is altogether tautological: what is cost of production to employers is (at the same time) income for factors of production. This (continuous or repetitive) relation- ship is illustrated in mainstream macro- economics textbooks by a simple diagram called the “circular flow” diagram, or model.

The circular flow model does allow for temporary discrepancies between income and expenditures, as when, for example, a portion of people’s incomes, especially of high incomes, is saved, not spent. But this would not seriously disturb the balance between aggregate incomes and expenditures because the savings would be borrowed (via banks and other financial intermediaries) and invested by manufacturers, thereby closing the temporary gap between aggregate income and spending. This means that, in a simple macroeconomic model, as long as aggregate national savings (S) are equal to aggregate national investment expenditures (I), that is, as long as “temporary leakages” from the circular flow are offset by injections of the same magnitude, an equilibrium between supply and demand would prevail.

In the conservative/neoliberal version of neoclassical economics the balance between S and I, and thus between aggregate income and spending, is restored/guaranteed by the forces of market mechanism: an excess of S over I would be only short-lived as this (temporary) oversupply of loanable funds would soon lead to lower interest rates, or lower borrowing costs, which would then encourage businesses/ manufacturers to borrow and invest more. This process of borrowing and investing the cheaper or undervalued S would continue until the excess S is used up and equality between S and I is restored.

In the liberal/Keynesian version of neo-classical economics, however, such a spontaneous or automatic restoration of balance between S and I cannot be guaranteed, which means that a situation of S>I, or insufficient investment spending relative to aggregate savings, could persist for a long time. Under conditions of relative market uncertain- ty, even low interest rates would not induce manufacturers to borrow and invest, or expand. Nor would holders/ owners of “idle” savings be willing to part with their savings when interest rates are too low; preferring, instead, to stay liquid in the hope of garnering higher returns when rates go up in the future – the often cited Keynesian term “liquidity trap” or “liquidity preference” was coined in this context. Under such conditions, the government could/ should step in, borrow the “idle” savings and spend them (“in behalf of their wealthy owners,” as Keynes put it), thereby closing the savings–investment (or income–expenditures) gap.

It is obvious from this brief picture that, according to neoclassical economics, the supply of credit and/or the volume of finance capital is determined or limited by the magnitude of aggregate supply/output, or national income; specifically, by the volume of national savings, which in turn is determined by the magnitude of national output.

Although the central bank’s policy of “fractional reserve banking” can stretch the volume of credit beyond the volume of savings, loanable finance capital is ultimately constrained by the total amount of national savings.

While this view of savings as the main source of credit or financing of real investment projects may have been true in the early stages of capitalism * (when the banks as financial intermediaries between savers and investors recycled “idle” savings into money capital for productive investment), it is no longer the case in the era of advanced capitalist economies in which well-established financial markets have become not only independent of but, in fact, dominant over the real or non-financial sector of the economy. The credit system in the mature and highly financialized market economies of today is no longer confined by domestic savings or central bank regulation of the money supply.

The institutional structure of the monetary/financial system which gives the commercial banks the power of creating money many times the amount of their reserves — by virtue of the so-called fractional reserve system — makes the supply of money much more flexible than domestic savings or formal central bank regulations permit. Commercial banks and other financial institutions are quite resourceful in expanding their lending capacity beyond their legal limits. The apparent idea behind these limits is that, based on the amount of their loanable deposits (as determined by “reserve requirements”), commercial banks first determine their lending capacity and then look for customers.

But the realities are quite the other way around. More than half of new business loans are made to big corporations under credit lines the companies have negotiated with their bankers, legally entitling them to borrow agreed-upon amounts. As one officer of the New York Federal Reserve has put it, “In the real world, banks extend credit . . . and look for reserves later. In one way or another, the Federal Reserve will accommodate them” [2].

Furthermore (and contrary to the neo- classical “circular flow” model), in the era of highly “financialized” capitalism demand for credit is not limited to industrial or commercial credit. In the age of well-developed stock markets, futures markets, real estate markets, commodities markets, derivatives markets, and similar markets for speculation, a large part of credit is demanded for speculative debt financing, or speculative investment. Under these circumstances, parasitic finance capital, feeding on itself by sucking out economic surplus/profits from the real sector, has effectively undermined the neat neoclassical “circular flow” mechanism – in which people’s savings and industrialists’ (retained) earnings are supposed to be recycled via financial intermediaries into productive investment. In the era of the dominance of finance capital, a large amount of the real sector’s profits-cum- savings that “leak out” of the income- expenditures circular flow into the financial sector never come back to be reinvested productively, as mainstream economic theory postulates. Instead, those savings are systematically syphoned off the real economy and invested in the unproductive, parasitic financial sector.

Many economists have argued that the escalating financialization of the past several decades has been prompted by the “lackluster” growth and/or “low” rates of return in the real sector of the economy [3]. Evidence shows, however, that capital flight from the real to the financial sector has continued even when profitability has been robust in the real sector. For example, real- sector profit rates in the U.S. economy were quite healthy during all of the four periods of 1983-87, 1993-2000, 2003-

Many economists have argued that the escalating financialization of the past several decades has been prompted by the “lackluster” growth and/or “low” rates of return in the real sector of the economy [3]. Evidence shows, however, that capital flight from the real to the financial sector has continued even when profitability has been robust in the real sector. For example, real- sector profit rates in the U.S. economy were quite healthy during all of the four periods of 1983-87, 1993-2000, 2003-

2007 and 2009-2013. Nevertheless, financialization continued unabated even during these periods of healthy profits; indicating that the lure of speculative profits, greatly facilitated by the extensive deregulation of the financial sector, has been strong enough to induce monetary capital to abandon manufacturing in pursuit of higher returns within the financial sector.

Capital flight from the real to the financial sector, and the divergence between corporate profitability and real investment were highlighted in an article by Robin Harding published on July 24, 2013 in the Financial Times. Headlined “Corporate Investment: A Mysterious Divergence”, the article revealed that a “disconnect” has developed between corporate profitability and real investment in the past three decades or so; indicating that, contrary to previous times, a significant portion of corporate profits is not reinvested for capacity building. Instead, it is diverted into financial investment in pursuit of higher returns to shareholders’ capital. Prior to the 1980s, the two moved in tandem — both about 9% of GDP. Since then, and especially in the very recent years, whereas real investment has declined to about 4% of GDP, corporate profits have increased to about 12% of GDP.

The systematic funneling of savings and profits away from the real to the financial sector has, indeed, been encouraged in recent years by the regulators: “In the past two decades most regulators have encouraged banks to shift assets off their balance sheets into SIVs [Special Investment

Vehicles] and conduits”, reported the Financial Times on February 5, 2008. Special Investment Vehicles and conduits, like Private Equity Groups, are part of a vast network of shadow (trading) banks that specialize in the buying and selling of companies, in managing/supervising with hedge, and in interacting and dealing with a whole host of other “financial engineering” services. Not surprisingly, the financial sector has been growing much faster in recent decades than the real sector of the economy, as it is increasingly absorbing larger and larger shares of national resources:

“In the real world most credit today is spent to buy assets already in place, not to create new productive capacity. Some 80 percent of bank loans in the English-speaking world are real estate mortgages, and much of the balance is lent against stocks and bonds already issued. Banks lend to buyers of real estate, corporate raiders, ambitious financial empire-builders, and to management for debt-leveraged buyouts” [Ibid.].

Prof Michael Hudson (of the University of Missouri, Kansas City) and a number of other financial experts have labelled the rapidly expanding financial sector the FIRE sector — standing for finance, insurance and real estate. Designation of the term FIRE conveys (understand- ably) a negative connotation, since the excessive expansion of this sector tends to re-allocate resources from productive to unproductive activities, to undermine the potential for real socio-economic growth and to further aggravate the already lopsided distribution of income and resources against the overwhelming majority of the people.

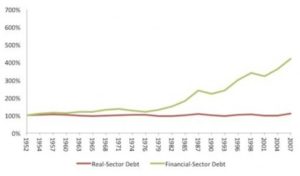

The figure below clearly shows this ominous trend: it shows that while bank lending to the FIRE sector as a share of GDP has quadrupled since the 1950s, the similar ratio for bank lending to the real sector has remained almost unchanged.

The following are a few additional examples of the astronomical growth of the FIRE sector during the past three decades or so: Between 1980 and 2005, profits in the financial sector increased by 800%, more than three times the growth in non-financial sectors. In the early 1990s there existed only a couple of hedge funds; by 2007, their number had grown to 10,000. The number of mortgage brokers, replacing old-style Savings & Loans and regional banks, has likewise mushroomed in recent years/decades: 50,000 thousand of them, employing nearly 400,000 brokers, more than the whole U.S. textile industry [4]. As the (unusually candid) manager of the hedge fund Raymond Dalio of Bridgewater Associates bluntly put it: “The money that’s made from manufacturing stuff is a pittance in comparison to the amount of money made from shuffling money around. Forty-four percent of all corporate profits in the U.S. come from the financial sector compared with only 10 percent from the manufacturing sector” [5].

As noted earlier, the neoclassical “circular flow” and/or “general equilibrium” model/theory is built on the basis of a near-barter economic paradigm, that is, an economy where money is implicitly treated as largely a means of exchange or circulation, not as an ideal or ultimate repository of the accumulated or concentrated wealth. In this model, financial cycles neatly follow real cycles: they expand when real cycles expand, and contract when they contract. As such, there is hardly any possibility for financial bubbles to emerge and expand independent of the real sector of the economy—the financial sector is treated essentially as a service or subsidiary sector to the real sector.

The circular flow model (like most other models) can, of course, serve as a useful tool or concept for analytical purposes. It is designed to show what happens when/if the circuit, or circular flow, breaks down, and what to do about it. The problem is that mainstream economists seem to have been stuck in the abstract model, in the earlier stages of capitalism, unable to see how in the era of giant banks and other colossal financial institutions finance capital can (and does) grow independent of industrial capital, thereby leading to financial inflations, followed by implosions.

It might be argued: who cares whether a financial bubble follows a real sector expansion or whether it is formed ab-ovo, i.e., in the absence of such an expansion. Such a distinction, however, is critically important to an understanding of how in the age of advanced financial markets finance capital has become largely independent of industrial capital, and how it has therefore undermined the neoclassical concepts of general equilibrium, of circular flow mechanism and of national savings as the main source of supply of money—in short, how it has rendered the neoclassical economists’ theory of credit creation, of investment financing and of money supply obsolete. Sucking financial resources from the rest of the economy, as well as generating fictitious capital out of thin air through speculation/gambling, parasitic finance capital feeds on itself—just like a real parasite. Neoclassical economists have not, so far, been able to reconcile the financial sector with their circular flow and/or general equilibrium model.

Sadly, instead of trying to incorporate the financial sector into their real sector model, they have chosen to ignore it lest it should disturb their shipshape, convenient model.

References

[1] This essays draws heavily on Chapter 3 of my book, Beyond Mainstream Explanations of the Financial Crisis.

[2] Robert Heilbroner and John Galbraith, Understanding Macroeconomics, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall 1990, P. 383.

[3] See, for example, Robert Brenner, “What is Good for Goldman Sachs is Good for America: The Origins of the Current Crisis,” http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/issr/cstch/papers/BrennerCrisisTodayOctober2009.pdf; Andrew Kliman, The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the Great Recession, Pluto Press 2011.

[4] Steve Fraser, “The Archeology of Decline: Debtpocalypse and the Hollowing Out of America,” TomDispatch.com, http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175623/.

Source: Counterpunch, 21 Nov 2014

http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/11/21/why-mainstream-economists-theory-of-finance-is-useless/

Ismael Hossein-zadeh is Professor Emeritus of Economics (Drake University). He is the author of Beyond Mainstream Explanations of the Financial Crisis ( 2014), The Political Economy of U.S. Militarism (2007), and the Soviet Non-capitalist Development: The Case of Nasser’s Egypt (1989).

* Editorial comment: A number of postKeynesian and MMT economists maintain that it was never true that savings are the main source of credit money or the financing of real world investment projects. The mainstream view is based on a materialistic (or more correctly barter-based ) view of capital as ‘stock’, as Adam Smith saw the matter (adopted from the French Physiocrats).