What exactly is all this productivity for?

David Ruccio

It’s a story that could have appeared in the pages of George Packer’s magnificent book, The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America. Or from the pen of Molly Ivins – which is good, since Esther Kaplan was recently awarded the 2015 MOLLY National Journalism Prize for her article, “Losing Sparta: The Bitter Truth Behind the Gospel of Productivity”.

The fact is, while Kaplan’s writing is superb, the story she tells about a plant that made commercial lighting fixtures in Sparta, Tennessee is an all-too- familiar one in contemporary America. Philips,”a multibillion-dollar multinational firm that sells everything from health- care equipment to home appliances across the globe,” bought the plant in 2008 and then, in 2010, announced the plant was closing, since Philips had decided to outsource most of its production to another of its plants, in Monterrey, Mexico. Unfortunately, the economic and social landscape of the United States is increasingly littered with the broken bodies and spirits of countless workers, their families, and the communities in which they live as a result of such corporate decisions.

What makes Kaplan’s essay interesting is that it operates at two different but related levels. She tells the story of the widespread devastation caused by Philips’s precipitous decision to close the Sparta plant, especially the difficult- ies both individual workers and the surrounding community have had attempting to replace the lost jobs. One of the best parts is her analysis of local attempts to purchase the plant and sell the lighting fixtures to Philips.

Much in the Sparta story defies the familiar political scripts: Norris, the union-avoidance expert, along with Bailey and Sullivan, of the Chamber of Commerce, joining hands with the IBEW to help save a union plant; small businessmen in Tea Party country championing community ownership.

It became clear from my conversations that Philips’s actions had deeply offended people’s sense of decency, from the laid-off workers to what Donna McCurry calls “the big wheels in town,” and that this sense of corporate indecency is what had brought such politically disparate people together.

(Both Packer and Ivins would have been proud to identify such political ironies.)

But Kaplan also thinks and writes at another level, grappling with the problem of productivity at the level of the plant and of the economy as a whole. In the case of the Sparta plant, workers had increased productivity (just as they continue to do, year in and year out, in the U.S. economy) and yet Philips decided to close the plant and relocate most of its production to a plant in Mexico (which had lower productivity but where workers received much lower wages and were not represented by a union).

One might be forgiven for asking what, exactly, all this productivity is for. “We busted our butts to get where we were at,” Ricky Lack [a maintenance worker at the plant] said the first time we spoke. “We got to number one. And it didn’t matter.”

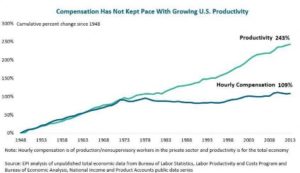

That turns out to be the key question – in individual plants (where, after the workers heed the call to increase productivity, they continue to face the threat of plant closures) and in the economy as a whole (in which since the mid-1970s productivity continues to increase but workers’ pay falls increasingly far behind).

Even today, mainstream economists and politicians continue to preach the gospel of productivity. Kaplan’s story is the bitter truth behind that gospel.

Source: Real-World Econ Rev Blog https://rwer.wordpress.com/2015/06/16/what-exactly-is-all-this-productivity-for/

Prof David Ruccio, PhD, is an economist at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana USA, where he has been teaching since 1982.